Conservatism as Skeptical Solution to Life

“Custom is the great guide of human life”

Part 1: Knowledge.

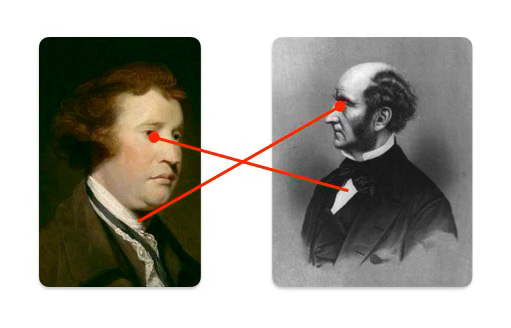

We all know the sun will rise tomorrow. This knowledge results from “reasoning from experience,” namely the experience of the sun’s rising each morning past. Such knowledge is “essential to the subsistence of all human creatures”: if your experience with bread left you helpless before the next baguette, unsure whether it would nourish or poison you, you wouldn’t last long. David Hume1 wondered how we pull these reasonings off. The core problem: in all such reasonings, “there is a step taken by the mind, which is not supported by any argument or process of the understanding.”

The step is from observing some regularity, to expecting it to continue. How did your mind acquire the propensity to take this step? Not by constructing a quasi-mathematical proof that regularities must always continue. The continuation of regularities is not necessary, so no such proof is possible, and anyway you had the propensity as a baby, long before you had the ability to produce proofs. Nor did the propensity result from (i) observing that, in the past, past regularities continued into the future, and (ii) concluding from this that current past regularities will also so-continue. You could make this inference only if you were already disposed to extrapolate past regularities, so the inference cannot explain the disposition. These are Hume’s “skeptical doubts concerning the operations of the understanding.”

To these doubts Hume proposed a “skeptical solution.” The mind is “induced” to “make this step,” that is, to extrapolate, not by some argument, or the operation of (what he calls) the understanding, but “by some other principle,” which he calls “Custom or Habit.” Today, we might say that the propensity to extrapolate has been built into us by natural selection; Hume said it was part of human nature.

Reason, which for Hume is but one of the mind’s many faculties, is, Hume concludes, somewhat feeble, and we are fortunate that other mental faculties help it along, or we would know very little indeed. We are fortunate, in Hume’s somewhat unfortunate terminology, that our reasoning from experience does not rely entirely on the faculty of Reason. Reasoning from experience “could [not] be trusted to the fallacious deductions of our reason, which is slow in its operations...[and] in every age and period of human life [is] extremely liable to error and mistake”:

As nature has taught us the use of our limbs, without giving us the knowledge of the muscles and nerves, by which they are actuated; so has she implanted in us an instinct, which carries forward the thought in a correspondent course to that which she has established among external objects.

Part 2: Well-being.

One form of conservatism is a simple attachment to the familiar, and consequent resistance to change. Another form is the assertion that such-and-such form of life and of society (fill in the blank: feudal, Christian, etc)—one that, as it happens, was realized in the past—is the right one, and is known to be right; we should, therefore, return to it. If the second form of conservatism is based on knowledge, a third form, the one of interest here, is based on skepticism. What Hume said about our capacity to know, this conservative says about our capacity to live well. Edmund Burke was this kind of conservative; explaining his opposition to the French Revolution, he wrote

We are afraid to put men to live and trade each on his own private stock of reason; because we suspect that the stock in each man is small, and that the individuals would do better to avail themselves of the general bank and capital of nations and of ages. Many of our men of speculation, instead of exploding general prejudices, employ their sagacity to discover the latent wisdom which prevails in them.

Joseph Henrich’s The Secret to Our Success is a book about culture and evolution, but really it is a secret case for Burkean conservatism. In a chapter titled “On the Origin of Faith” he discusses the starch-rich tuber manioc, which in several parts of the world is a dietary staple. If eaten unprocessed, manioc “can cause both acute and chronic cyanide poisoning.” To solve this problem the Tukanoans, a society in the Columbian Amazon,

use a multistep, multiday processing technique that involves scraping, grating, and finally washing the roots in order to separate the fiber, starch, and liquid. Once separated, the liquid is boiled into a beverage, but the fiber and starch must then sit for two more days, when they can then be baked and eaten.

This process reduces the cyanide to a negligible, safe level. But that is not why the Tukanoans do it. Removing cyanide is not the explanation they offer for their behavior. They do it out of custom or habit. They cook manioc that way, simply because their parents cooked manioc that way. Henrich elaborates:

despite [the process’s] utility, one person would have a difficult time figuring out the detoxification technique. Consider the situation from the point of view of the children and adolescents who are learning the techniques. They would have rarely, if ever, seen anyone get cyanide poisoning, because the techniques work.... Most people would have eaten manioc for years with no apparent effects. Low cyanogenic varieties [of manioc] are typically boiled, but boiling alone is insufficient to prevent the chronic conditions for bitter varieties. Boiling does, however, remove or reduce the bitter taste and prevent the acute symptoms (e.g., diarrhea, stomach troubles, and vomiting). So, if one did the common-sense thing and just boiled the high-cyanogenic manioc, everything would seem fine. Since the multistep task of processing manioc is long, arduous, and boring, sticking with it is certainly nonintuitive. ...

Now consider what might result if a self-reliant Tukanoan mother decided to drop any seemingly unnecessary steps from the processing of her bitter manioc. She might critically examine the procedure handed down to her from earlier generations and conclude that the goal of the procedure is to remove the bitter taste. She might then experiment with alternative procedures by dropping some of the more labor-intensive or time-consuming steps. She’d find that with a shorter and much less labor-intensive process, she could remove the bitter taste. Adopting this easier protocol, she would have more time for other activities, like caring for her children. Of course, years or decades later her family would begin to develop the symptoms of chronic cyanide poisoning.

Thus, the unwillingness of this mother to take on faith the practices handed down to her from earlier generations would result in sickness and early death for members of her family. Individual learning does not pay here, and intuitions are misleading. The problem is that the steps in this procedure are causally opaque—an individual cannot readily infer their functions, interrelationships, or importance.

The Burkean conservative holds that life-plans handed down through custom are similarly opaque. Following them is in fact a path to happiness and fulfillment. The person who is choosing how to live, however, can easily see the plans’ drawbacks, and not easily see their benefits. If you sit in your armchair, and compare them to other possible life-plans you might pursue, and try to figure out which will be better, you will likely reach the wrong conclusion. If Hume held that Reason alone can produce little by way of knowledge, Burke held that reasoning about which life is best will produce little by way of well-being. In both cases the solution is the same: follow custom or habit, a process or plan handed down through generations of refinements, which ahead of time you cannot justify.

Part 3: Liberalism.