“Conservatives are opposed to Reason”: a good summary, if one that makes for bad PR. Does it become more appealing when we trade excitement for accuracy?

1. In one sense of the phrase, conservatives oppose reason because they tend toward skepticism. But theirs is not a global skepticism, thank goodness—we know a lot! Their doubts are specific and their target is limited, to armchair investigations of institutional quality. You may think that your hours of bookish research have revealed the ideal constitution for a nation-state, or the perfect interventions for solving social problems. But you’re probably wrong, the conservative says; and if you’re right, you’re right by chance. We can reason our way to knowledge in many domains; but not here.

These doubts do not extend to more indirect and more empirical methods of investigating governments and social practices. Systems that have been produced by a long evolutionary process, in which “each new generation makes a slight improvement to what it has received [and] then hands it down to the next,” tend toward justice, and the promotion of the common good; and we can know this. That’s why conservatives defer to and defend tradition. But this sophisticated reasoning is “not really a full-blooded defense of tradition.” Instead,

it is a rational argument in favor of deferring to tradition... it does not claim that tradition is always right...It says that in specific instances, reason is likely to do a bad job at figuring things out, so we may be better off relying on evolutionary processes. (Joseph Heath, Enlightenment 2.0.)

Yuval Levin repeats the point in The Great Debate: Edmund Burke, Thomas Paine, and the Birth of Right and Left. Explaining Burke’s conservatism, he writes that Burke

sees tradition as a process with something of the character that modern biology ascribes to natural evolution. The products of that process are valuable not because they are old, but because they are advanced—having developed through years of trial and error and adapted to their circumstances. (emphasis added)

Of course, conservatives do not think that old traditions are necessarily advanced. Just like you, they can locate, and will acknowledge, plenty of long-standing evils and injustices in the historical record. But long-standing traditions should, they assert, be given the benefit of the doubt.

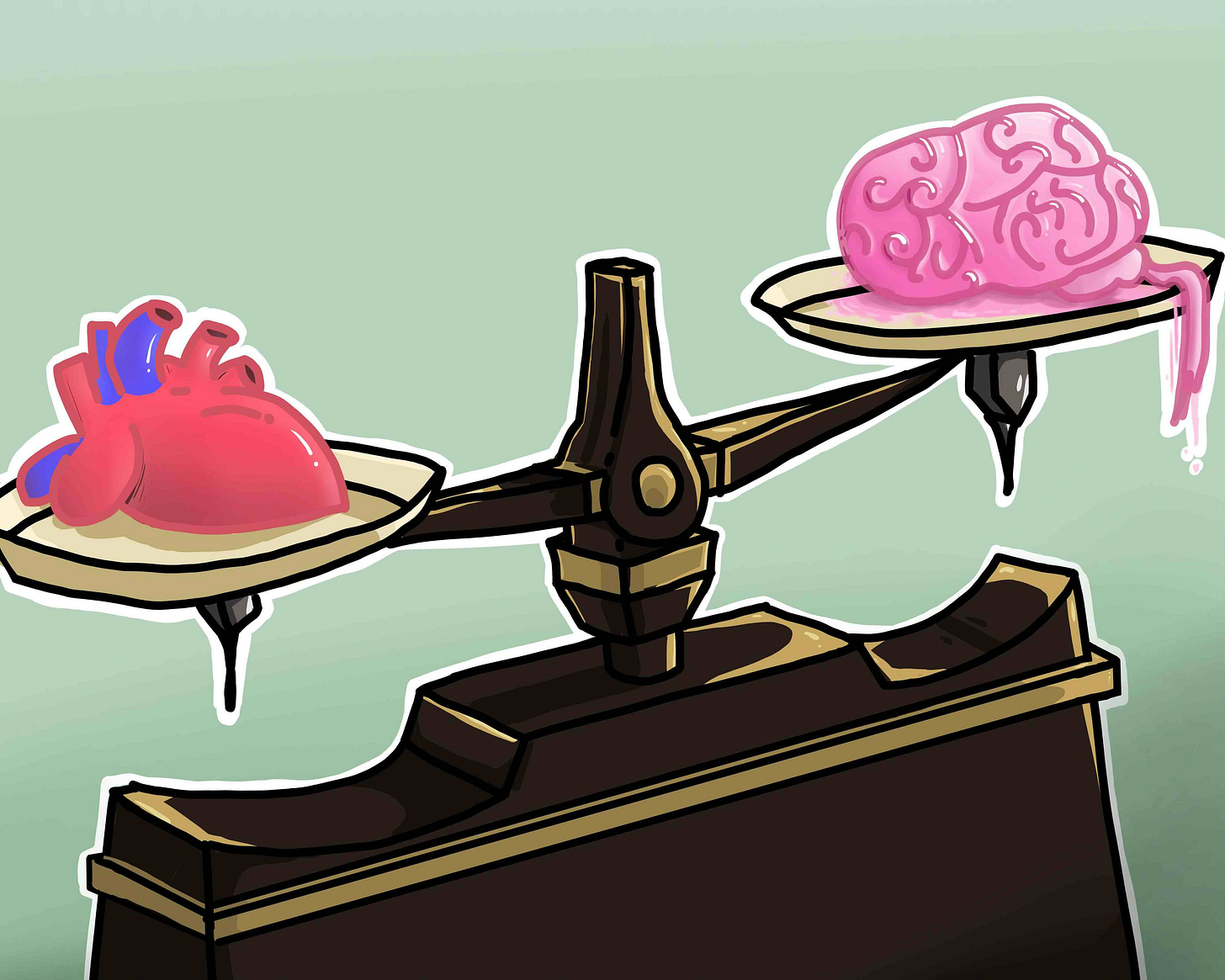

2. So far, conservatism look like a piece of applied epistemology. That’s misleading. Conservatism is more than a doctrine about what can be known, and how; it’s a political philosophy.

But political consequences do follow from conservative skepticism. That skepticism justifies an opposition, characteristic of conservatives, to fast and far-reaching changes to our social and political institutions. If there’s no way to know ahead of time whether those changes will be improvements; if they’d likely make things worse; if, the status quo, being old, likely has something going for it, and if its benefits may be “latent” and hard to discern; then it’s better to stick to what’s been working, and limit our ambitions for improvement to a cautious exploring of small revisions.

But skepticism is not the only motive for conservative opposition to radicalism. That opposition would survive skepticism’s defeat, even its disarming. If God, or the oracle of philosophy, revealed to us that a society that lived by institutions and practices quite different from our own was, by both the measures of justice and of the general welfare, doing better than we were, conservatives would still oppose the immediate replacing of our constitution with theirs. Why is that?

Maybe they have many answers. But one of them surely starts from the fact that rules are one thing, compliance with them another. Here is a second place where conservatives oppose reason. They doubt that people will participate willingly in a social order, and comply with the law, solely on the ground that they grasp, rationally, that that law and order are just. Sentimental attachment, loyalty, love—for one’s country, its ways of doing things, and its great leaders past and present—these emotional motives for cooperation are much stronger. You can surely find in your own life small-scale examples of this. My bank was recently bought by a bigger bank. I was loyal to the old one; I’d go to it first if I needed a loan. The new one is a stranger to me, and has no special standing in my decisions. This, from so small a change! The buildings are the same, most of the people are the same. Now imagine self-proclaimed enlightened revolutionaries giving you and your compatriots a new constitution. The conservative says: if they do that, then to secure compliance they’ll need to rely mostly on punishment, and the fear of punishment. And the more a state must rely on punishment to secure compliance, the more it tends toward injustice. Maybe this is what Burke was getting at when he wrote, about the new order being built on the French revolutionaries’ “barbarous philosophy,” that in it

laws are to be supported only by their own terrors, and by the concern which each individual may find in them from his own private speculations, or can spare to them from his own private interests. In the groves of their academy, at the end of every vista, you see nothing but the gallows. Nothing is left which engages the affections on the part of the commonwealth. On the principles of this mechanic philosophy, our institutions can never be embodied, if I may use the expression, in persons—so as to create in us love, veneration, admiration, or attachment. But that sort of reason which banishes the affections is incapable of filling their place. (Reflections on the Revolution in France)

See also Conservatism as Skeptical Solution to Life, and The Coming of the Reign of Terror.

Below the fold, for premium subscribers: a note on conservatism and the American revolution, and a remark on the problem of motivation in liberal political thought.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mostly Aesthetics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.