1: The Arion Press edition of Moby-Dick was as monumental as the novel, “entirely set by hand” and “printed on dampened handmade paper by a platen letterpress,” the pages a gigantic 15 x 10 inches in size.1 Selling for $1000 (in 1979 dollars), only 265 were ever made. Andrew Hoyem, the project’s mastermind, hired Barry Moser to illustrate the book, but under strict instructions, strictly-enforced:

no dramatic or interpretive scenes would be imposed on the reader’s imagination…the text would be interspersed with informative depictions of subjects mentioned by Melville…New Bedford, whales and harpooning will be shown, but the Pequod, Ahab and Moby-Dick will be described only in Melville’s words.2

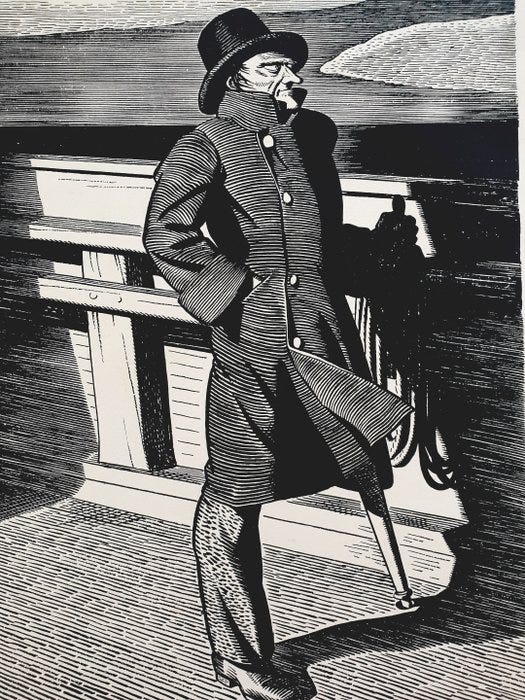

Moser came to resent these rules, but Hoyem was right. The question of why one should read a novel when a film version exists has an answer: the film, unlike the book, has to show how the characters look, and that can make a story worse—not because the actor doesn’t match every readers’ vision of a certain character, but because the story draws its power partly from the character being unvisualized, even unvisualizable. If any character is like that, it is Captain Ahab, whom Melville describes, variously, like this:

He looked like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them, or taking away one particle from their compacted aged robustness.

Captain Ahab stood erect, looking straight out beyond the ship’s ever-pitching prow. There was an infinity of firmest fortitude, a determinate, unsurrenderable wilfulness, in the fixed and fearless, forward dedication of that glance.

moody stricken Ahab stood before them with a crucifixion in his face; in all the nameless regal overbearing dignity of some mighty woe.

Draw that!

The most famous illustrated edition of Moby-Dick—Lakeside Press, 1930—illustrates the point. No matter how powerful Rockwell Kent’s Ahab, too much is lost giving him any definite visual character at all. The larger-than-life becomes merely life-sized:

2: John Bryant, in "Moby Dick as Revolution,"3 recounts the "legend”

that there are two Moby-Dicks. The first would be nothing more than 'a romance of adventure founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries' [as Melville put it to his British publisher].

Melville was mostly finished with this version when he met Nathaniel Hawthorne; a meeting, which, combined with Melville’s “absorption of Shakespeare,” allegedly

triggered a significant reorientation of Moby-Dick. [The original Moby-Dick was to be] a narrative of whaling fact ... [that] would involve Ishmael, Queequeg, and such strange characters as Peleg, Bildad, and Bulkington, but not Ahab. However, sometime after the August encounter with Hawthorne, Melville recast the book entirely to include the Shakespeareanized story of Ahab.

Melville tried to "splice" the new story in with the original, but

the seams still showed, [and] with a deadline to meet and family to feed, Melville surrendered the novel to his printer, telling Hawthorne that all his works were 'botches,' Moby-Dick included.

Regarding this “legend,” Bryant tells us that "there is little concrete evidence, and nothing at all conclusive, to show that Melville radically altered the structure or conception of his book," but even if there were, who cares? The genetic fallacy is a fallacy. Details of the book’s origins may matter to biographers, but if one is judging the story as a story, either it works or it doesn't, however it came to be.

But...the novel is indeed weird, and such speculations are understandable:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mostly Aesthetics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.