Holy Sonnet XIV

An artwork is better if it’s unified—its parts working together for a single end. If this definition is fuzzier than you like, is greater precision possible? The philosopher Monroe Beardsley, in his massively-comprehensive opus Aesthetics, did no better: unified works, he wrote, “contain nothing that does not belong; it all fits together.” This may be informative enough, because we know unity when we see it, but still, there’s value in looking, and in analyzing what we see.

Of John Donne’s Holy Sonnets, number XIV might be the best:

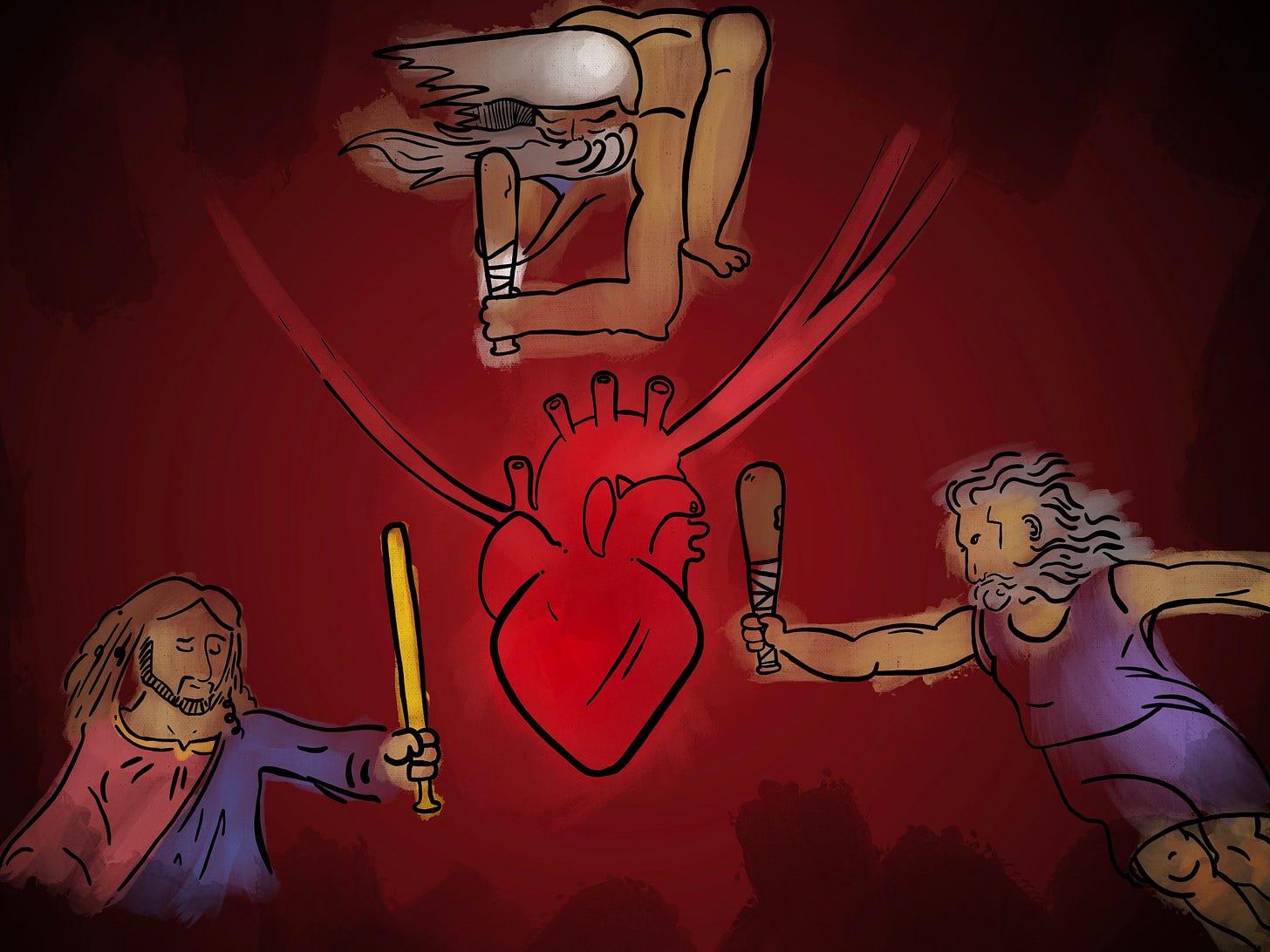

Batter my heart, three-personed God; for you As yet but knock, breathe, shine, and seek to mend; That I may rise and stand, o'erthrow me, and bend Your force to break, blow, burn, and make me new. I, like an usurped town, to another due, Labor to admit you, but Oh, to no end! Reason, your viceroy in me, me should defend, But is captived, and proves weak or untrue. Yet dearly I love you, and would be loved fain, But am betrothed unto your enemy; Divorce me, untie or break that knot again, Take me to you, imprison me, for I, Except you enthrall me, never shall be free, Nor ever chaste, except you ravish me.

A repetition of three-ness unifies the poem. Behold all the triples: God is “three-personed”; God’s acts, in line 2, are a trio of monosyllables: “knock, breathe, shine”; and two lines later, another trio, for the acts requested of God: “break, blow, burn.” On a larger scale, the poem develops three metaphors for God’s redemption, in each of its three sections—quatrain, quatrain, sestet. The metaphors escalate, and townspeople laboring fruitlessly to admit God give way, in the climax, to a lover asking God’s violation.

How deep does this unity go? Some say that each act in each three-itemed list is the act of a different one of the Divine Persons, who does what is appropriate to His character: the Father knocks, and is asked to break; the Son breathes, and is asked to blow; the Holy Spirit shines, and is asked to burn. There’s something to this, as the second acts intensify the corresponding acts in the first: a violent knock will break, a brighter shine will burn, and so on. But no, this is over-reaching, the stuff of a too-stoned grad student writing on seminar-deadline. The theology is too speculative; and, the poem’s emotional and devotional punch doesn’t care whether, or how, the labor is divided.

Was it already overreaching, to find three metaphors for redemption? Two are clear: the sinner as an “usurped” town, and the sinner as a lover desiring to be “enthralled” and “ravished.” If there’s a third, it’s in the first quatrain. Some can’t find one there at all, and call it a flaw in the poem: the first four lines express no clear conceit but only vaguely suggest “the destruction which is the prerequisite for atonement.” Others read the conceit in the second quatrain back into the first. If the sinner is a town that desires God’s conquest, he will certainly regard knocking as insufficient, and request the use of forces powerful enough to overwhelm the usurper’s defenses: breaking, blowing, burning. But this doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. A tentative, polite, and hesitant conqueror may well knock at the gate; but, on this interpretation, he’s also said to breathe and shine, which make no sense. I favor the view that there is indeed a distinct metaphor in the first quatrain, and so the poem does indeed instantiate three-ness in the large: God is a metal-worker, or perhaps a potter, and the sinner is the artifact He is working. Knocking, breathing on, and shining are not enough to make him what him ought to be; breaking, blowing, and burning, to begin again from the raw materials, are required.

See also: Two ways to read a poem; The Consolations of George Herbert.