George Herbert was a favorite of Coleridge’s: “I find more substantial comfort, now, in pious George Herbert’s ‘Temple’...than in all the poetry since the poems of Milton.” When I first read Herbert’s poetry, in college, I found comfort in it as well. Coleridge also wrote that appreciating the merits of the poetry required “a sympathy with the mind and character of the man [that is, Herbert]”; W. H. Auden, quoting this, responded that his “own sympathy is unbounded.”

I wanted to understand why Herbert’s poems had so affected me, so I re-read them, and dipped into the critical parts of George Herbert and the 17th Century Religious Poets: a Norton Critical Edition. (Herbert died in 1633.)

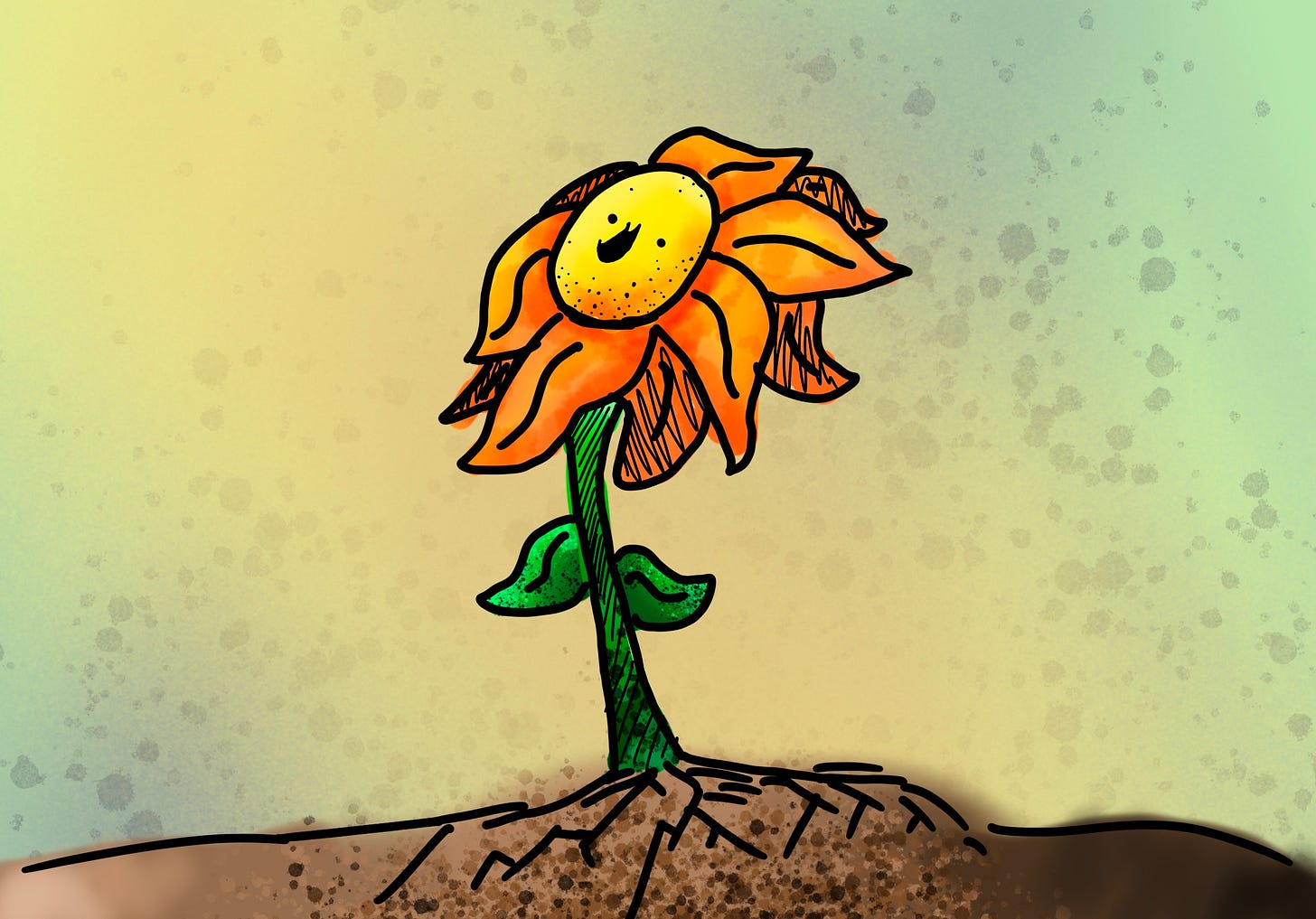

The essay by L. C. Knights selected for the book focuses on the patterns of emotional expression in Herbert’s poetry. In some places, Herbert’s verses express dejection and feelings of worthlessness; in others, acceptance and a “release from anxiety.” The Flower, Knights says, is the poem in which “the sense of new life springing from the resolution of conflict is most beautifully expressed.” The poem begins,