American Impressionist

As a concept, “American Impressionism was always oxymoronic, like, say, Canadian salsa”: surely this sentence is too good to be true?

Not long before reading it, I’d wandered into the “American Impressionism” room at the Boston MFA, and encountered Childe Hassam’s Boston Common at Twilight (1886). It’s a large work, and small reproductions don’t do it justice:

What’s not to like? The glow on the horizon; the distant streetlights at the far edge of the Common; the Bostonians lingering on a beautiful day, in defiance of the too-early winter sunset.

But Peter Schjeldahl made me doubt. (Quotations are from his 2004 review of a Childe Hassam retrospective.) Maybe my affection was less about the painting’s artistic merit, and more about its subject matter. Repeated exposure can make us Americans think that Great Paintings of Real Places must feature notable European cities, humble European landscapes, or else exotic locales further East:

So what a pleasure to find nearby Boston Common hanging in a museum, and to find a museum-worthy artist painting places that I visit in the ordinary business of life.

What’s Schjeldahl’s case against Hassam? First, that his work is “not quite Impressionism”:

Hassam painted sumptuous street scenes of strolling citizens at twilight…often generating pleasant tensions between fleeing perspective and brushy surfaces. These were credible instances of a not quite academic, not quite naturalist, not quite Impressionist international style.

Naturally, one wants to know what is missing. The “Canadian salsa” joke suggests that, in Schjeldahl’s view, True Impressionism requires some je ne sais quoi which may only be found in the blood of the native-born French. He doesn’t think that, but he does think there is more to Impressionism than the way the paint lies on the canvas. Artistic styles are like human beings—they have a surface, yes, but also a soul: “the spiritual drive of French Impressionism was an appetite for sensuous intensity”; it exhibited “a commitment to method that didn’t cultivate effects but discovered them.”

Americans like Hassam, who tried to learn the style, missed this, and so could only pantomime its effects:

It was the misery of American Impressionists to chase the look of French painting and yet remain numb to both its radical hedonism and its tough-minded gravity.

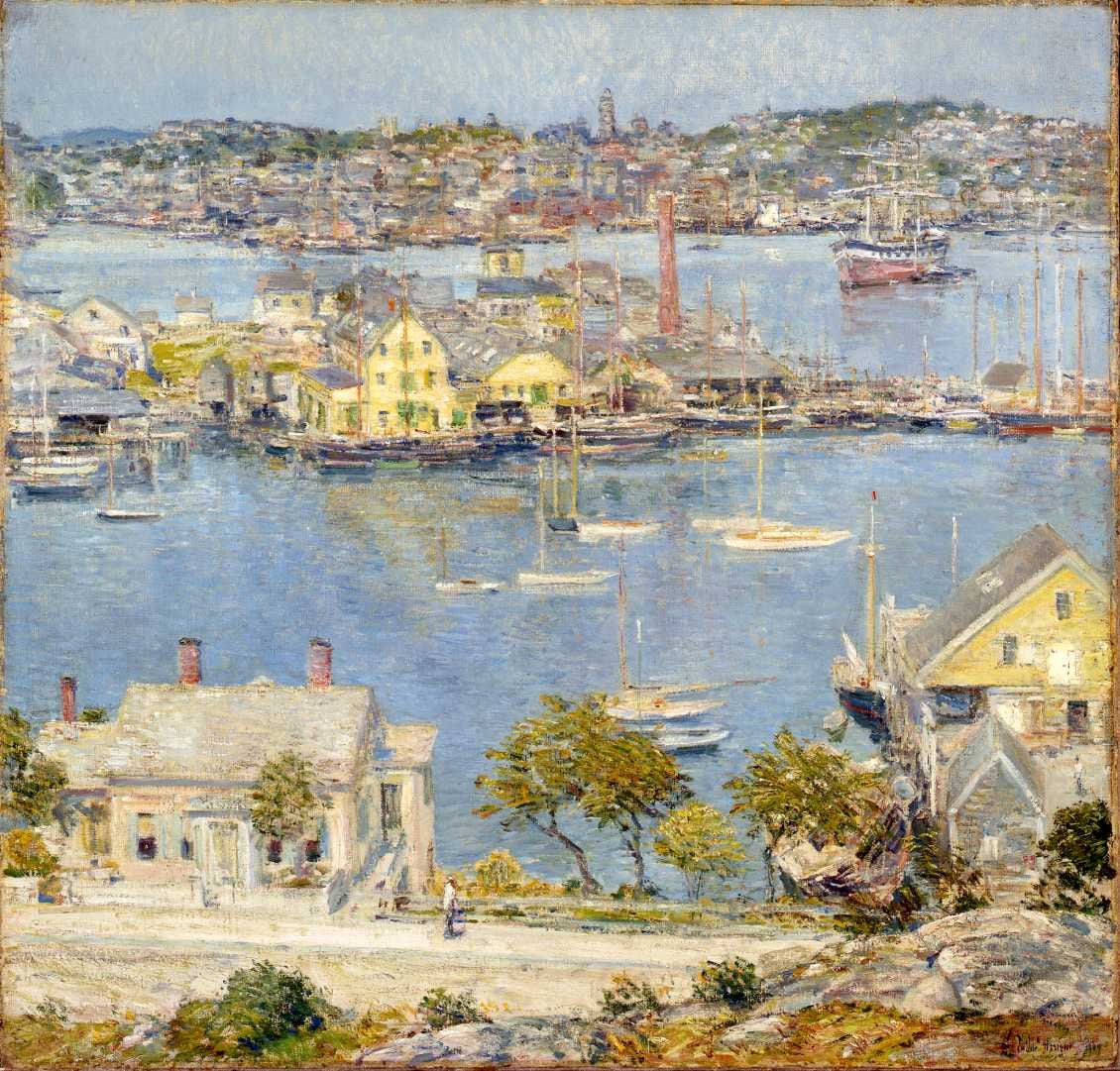

Schjeldahl does find high points in Hassam’s body of work. The paintings of Gloucester Harbor “convey personal enthusiasm for a practical-minded place that may be oblivious to its own drowsily cascading summertime splendor.”

(Gloucester is on Massachusetts’ other, underrated, cape, Cape Anne.) And Hassam’s paintings of a “flag-bedizened New York” deserve their popularity: the “patriotic mood feels wholly authentic.”

These paintings finally have the energy and drive toward abstraction that the Boston scenes lack. In an irony that goes unremarked, Schjeldahl says that with this most American of subjects, Hassam achieves “something like Impressionism at last”:

The blurred and splintered forms of his flag paintings shiver ecstatically, piling up compositions that collapse perspective into the forward-rushing, all-at-once tumult of a fever dream.

See also: On Georgia O’Keeffe; Notes on Japonisme.

I understood the Schjeldahl quote differently. I assumed he meant that to divide Impressionism into nations was odd, like talking about Iranian physics or Irish chemistry. There is only one kind of physics, chemistry and Impressionism...though having now read on, I now suspect your interpretation was right.

I love that room at the MFA!