Notes on Japonisme

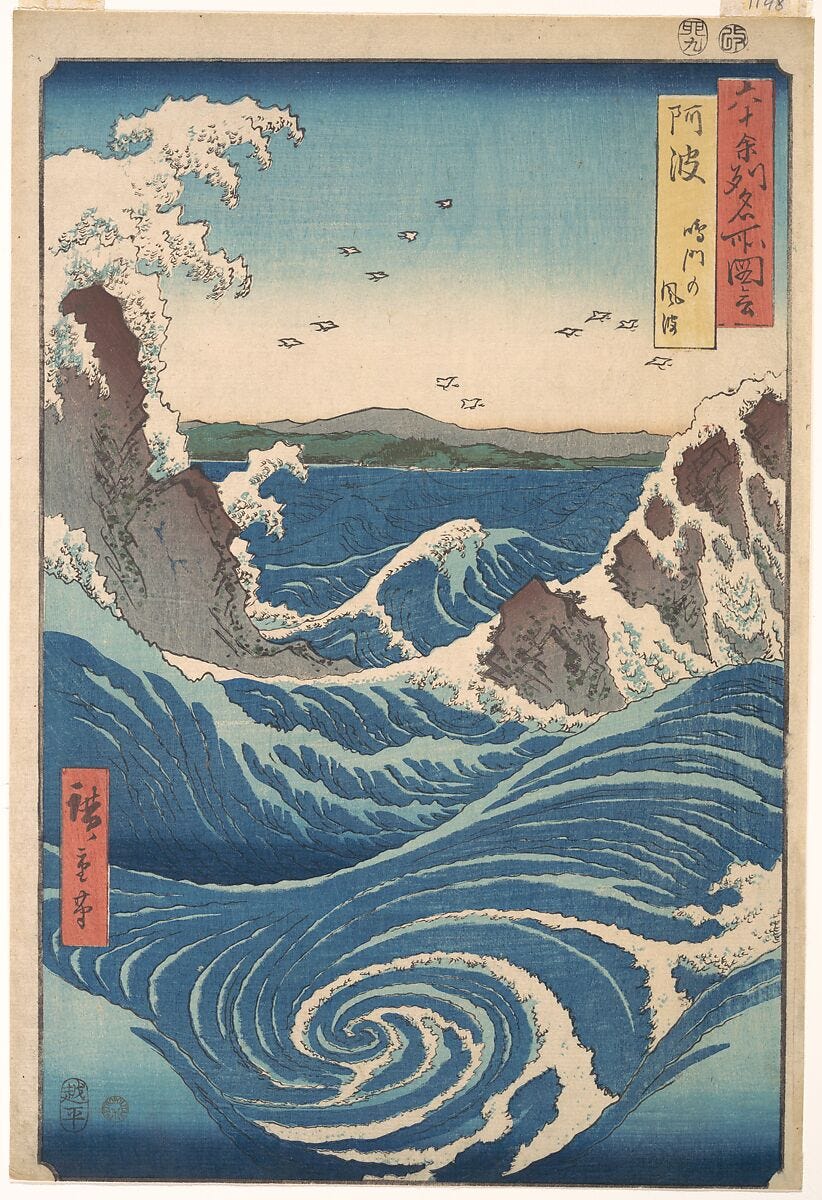

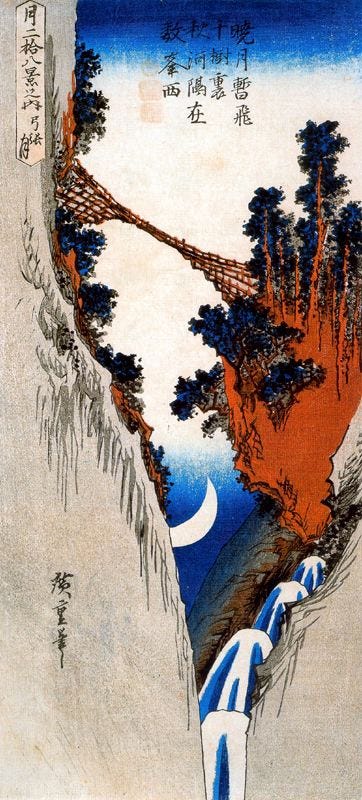

European painting had pursued “naturalistic illusionism” since the Renaissance. Japanese art had different ideals. Rather than using perspective, light, and shadow, to create the appearance of depth, Japanese prints and paintings tended toward “flatness.”

Japanese art also favored

The partial view, the view as from a very great height, the suspension of figures in space without a background,

all of which flouted the conventional European rules of composition.

In the late 19th century, European encounters with and adoption of Japanese techniques “hastened the birth of abstraction.” But why did these techniques draw the attention of Manet, Degas, Van Gogh? The massive catalogue Japonisme, by Siegfried Wichmann, carefully traces each line of influence, but says only a little about this most important question. Did artists feel they had exhausted the formal possibilities of naturalism, and saw in Japanese aesthetics new forms for them to explore? If so, their interest in Japanese aesthetics was purely “internal.” But psycho-historical motives were also possible. Perhaps these artists had new things to say or express, and existing conventions were not well-suited for their expression; and perhaps Japanese aesthetics was.

On the internal/formal side, Wichmann observes that