Young American

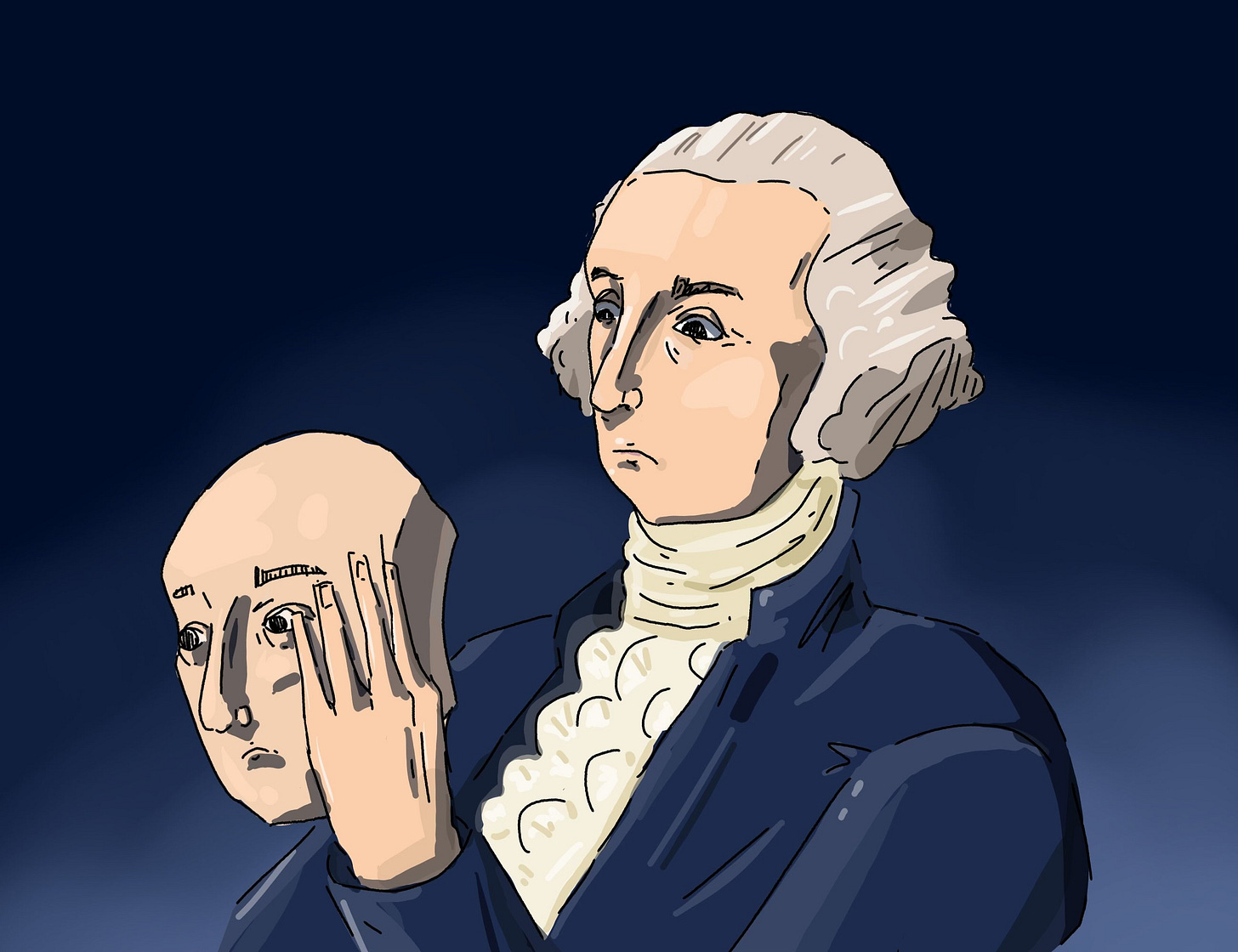

George Washington’s complete writings run past thirty-nine volumes, a bit much even for the father of a country. So it risks selection bias, to use the single volume devoted to him in the Library of America, to judge the arc of his career. That qualification made, Washington-in-command, the General Washington of 1775, seems quite changed from the gentleman-planter who wrote his letters just a few years earlier.

The pre-war Washington impresses us as a vain and somewhat shady real estate guy. Sure, standards of virtue have shifted over the last 250 years, but that cannot be the whole cause of our response. Look—in 1767 he wrote this to a friend, to solicit aid in buying land:

It will be easy for you to conceive that Ordinary, or even middling Land would never answer my purpose or expectation....No: A Tract to please me must be rich...Could such a piece of Land as this be found you would do me a singular favour in falling upon some method to secure it immediately from the attempts of any other.

Now successfully elbowing others aside might require creative accounting; if so, Washington was all for it:

It is possible...that Pennsylvania Customs will not admit so large a quantity of Land as I require, to be entered together; if so this may possibly be evaded by making several Entrys to the same amount...but this I only drop as a hint leaving the whole to your discretion....keep this whole matter a profound secret.

Above all, though, the whole project must be kept on the down-low:

[other, competing bids for the land] may be avoided by a Silent management and the Scheme snugly carried on by you under the pretence of hunting other Game.

I do love that phrase, “snugly carried out.” Now of course, when Britain clamped down on Massachusetts, in the lead-up to the War for Independence, it did not escape Washington’s notice. And he was always on the side of the rebels. 1774 finds him writing that the British “are endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavery upon us.” Washington argued that petitions for redress were pointless, in language that departed from his usual formal restraint, and approximated the Old Testament rhythms of Samuel Adams:

shall we after this whine and cry for relief, when we have already tried it in vain? Or shall we supinely sit, and see one Provence after another fall a Sacrifice to Despotism?

But that year also found him telling a friend, who had heard rumors that the Massachusetts rebels favored independence, that the rumors were categorically false, and his friend “grossly abused.” Indeed, Washington said he’s as sure of this as he “can be of my own existence”: cogito, ergo falsus. Samuel Adams had persuaded himself of the need for independence around 1767; on this crucial question, Washington was not ahead of the curve.

So none of what Washington wrote before 1775 prepares you for the letters he came to write, once he became the commanding general of the continental army, and de facto head of the rebellion. In Philadelphia, after the war had begun, just before he was named commander in chief, he wrote,

Unhappy it is though to reflect, that a Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s breast, and that, the once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with Blood, or Inhabited by Slaves. Sad alternative! But can a virtuous Man hesitate in his choice?

So Washington took charge of the rag-tag militiamen in Cambridge (my fair city), squinting across the river at General Thomas Gage, who commanded the British Regulars in occupied Boston. Washington wrote Gage to ask that he treat American POWs with respect. Gage, in his reply (which I have not read—it’s not in the book), sneers down at Washington, calls the Americans vicious traitors, and reserves all virtue and nobility for the British side of the dispute. It’s here, in his response, that the Washington of myth appears in real words on the page:

...Whether British, or American Mercy, Fortitude, & Patience are most preeminent; whether our virtuous Citizens whom the Hand of Tyranny has forced into Arms, to defend their Wives, their Children, & their Property; or the mercenary Instruments of lawless Domination, Avarice, and Revenge best deserve the Appellation of Rebels...Whether the Authority under which I act is usurped, or founded on the genuine Principles of Liberty, were altogether foreign to my Subject. I purposely avoided all political Disquisition; nor shall I now avail myself of those Advantages, which the sacred Cause of my Country, of Liberty, and human Nature give me over you.

It’s been said that Washington, while no dunce, did not have the mind of a Hamilton or a Jefferson. But this is brilliant rhetoric, for of course he is availing himself of the Advantage he has, of standing on the moral high ground. Later, addressing Gage’s implication that Washington is not worthy of his post, nor a worthy opponent of a British general, we see, not a man who subterfuges to increase his riches, but a man standing openly with and for his people:

You affect, Sir, to despise all Rank not derived from the same Source with your own. I cannot conceive any [rank] more honorable, than that which flows from the uncorrupted Choice of a brave and free people—the purest Source & original Fountain of all Power.

The letter ends with a kiss-off:

I shall now, Sir, close my Correspondence with you, perhaps forever...

Washington only appears a few times in American Independence in Verse. Partly that’s the time period: the book ends with independence, just when Washington became the main character. But I must admit intimidation as another cause. Writing the Adams cousins, and Thomas Paine, and even Thomas Jefferson (in pamphlet mode), was a challenge I felt up to; I wasn’t sure I was ready for George Washington.

American Independence in Verse is available for pre-order now.