Romanticism, I: Revaluation of Values

The Roots of Romanticism by Isaiah Berlin

Romanticism was, in Berlin’s account and others’—it’s a cliche—a reaction to Enlightenment Rationalism.

Rationalism, sometimes, is just an optimism about the possibility of knowledge, especially in social, moral, and political affairs. Euclid showed that, and how, secure knowledge was possible in geometry; much later, Newton did the same for physics. Could there be a similar science of humanity? What is our nature? How should we live? What customs and institutions make for a good society, and a good government? These questions too have answers, rationalists thought; answers that, if we investigate rightly, we can come to know.

These claims about Reality and Knowledge were bundled, in rationalism, with a claim about Virtue: virtue is knowledge. The virtuous person knows the facts about his situation, knows (the objective truth about) what that situation calls for, and is moved to act accordingly.

Whether any of this is right, shouldn’t we hope it’s right? We could discover Utopia; we could create or anyway approximate it here. But Berlin’s rhetoric is equivocal. The essence of rationalism, he says, is that “there is a body of facts to which we must submit.” To submit to a body of facts one cannot change: one cast of mind may find this a relief, but another rebels against it; another cries freedom! and raises up its sharpened axe. Maybe you feel its pull.

The most conservative anti-rationalism says that society and human nature and too complex, and each of us too small, for very much useful knowledge of those topics to be possible. But—there is still a “way things are.” Romanticism, in Berlin’s telling, is a far more radical doctrine, bordering on the mystical:

there is no external check, there is no structure which you must understand and adapt yourself to before you can proceed.

If the claim is that we have no nature, then it is baffling. A better interpretation is the existentialist one: our nature is what we make it. We do have a nature, but it is not an “external check”; it is not a constraint on how we should live. For (Berlin’s) Romantics, the answer to how should we live is not written in the sky to be discovered; we write it ourselves (let the Romantic rhetoric flow) in our own souls.

Romanticism consequently holds up different attitudes and traits as virtues. Virtue is not responding correctly to the (given) facts. Virtue is the creation of value; and also virtue is living up to the values one creates, however much they diverge from the values of others. It’s a kind of relativism: my values are no better or worse than yours; they may be compared, but they may not be judged. On this point, Berlin really gets into it:

The values to which [the Romantics] attached the highest importance were such values as integrity, sincerity, readiness to sacrifice one’s life to some inner light, dedication to some ideal for which it is worth sacrificing all that one is, for which it is worth both living and dying. You would have found that they were not primarily interested in knowledge, or in the advance of science ... not interested, above all, in adjustment to life, in finding your place in society, in living at peace with your government, even in loyalty to your king, or to your republic. You would have found that common sense, moderation, was very far from their thoughts. You would have found that they believed in the necessity of fighting for your beliefs to the last breath in your body, and you would have found that they believed in the value of martyrdom as such, no matter what the martyrdom was martyrdom for. You would have found that they believed that minorities were more holy than majorities, that failure was nobler than success, which had something shoddy and something vulgar about it. The very notion of idealism ... the state of mind of a man who is prepared to sacrifice a great deal for principles or for some conviction, who is not prepared to sell out, who is prepared to go to the stake for something which he believes, because he believes in it—this attitude was relatively new. What people admired was wholeheartedness, sincerity, purity of soul, the ability and readiness to dedicate yourself to your ideal, no matter what it was.

Again, in Romanticism

there is admiration ... for defiance as such ... for every kind of opposition to reality, for taking up positions on principle where the principle may itself be absurd; the fact that this is not regarded with the kind of contempt with which you regard a man who says twice 2 is 7, which is also a principle, but which nevertheless you know to be the assertion of something false—this is significant. What Romanticism did was to undermine the notion that in matters of value, politics, morals, aesthetics there are such things as objective criteria which operate between human beings, such that anyone who does not use these criteria is simply either a liar or a madman.

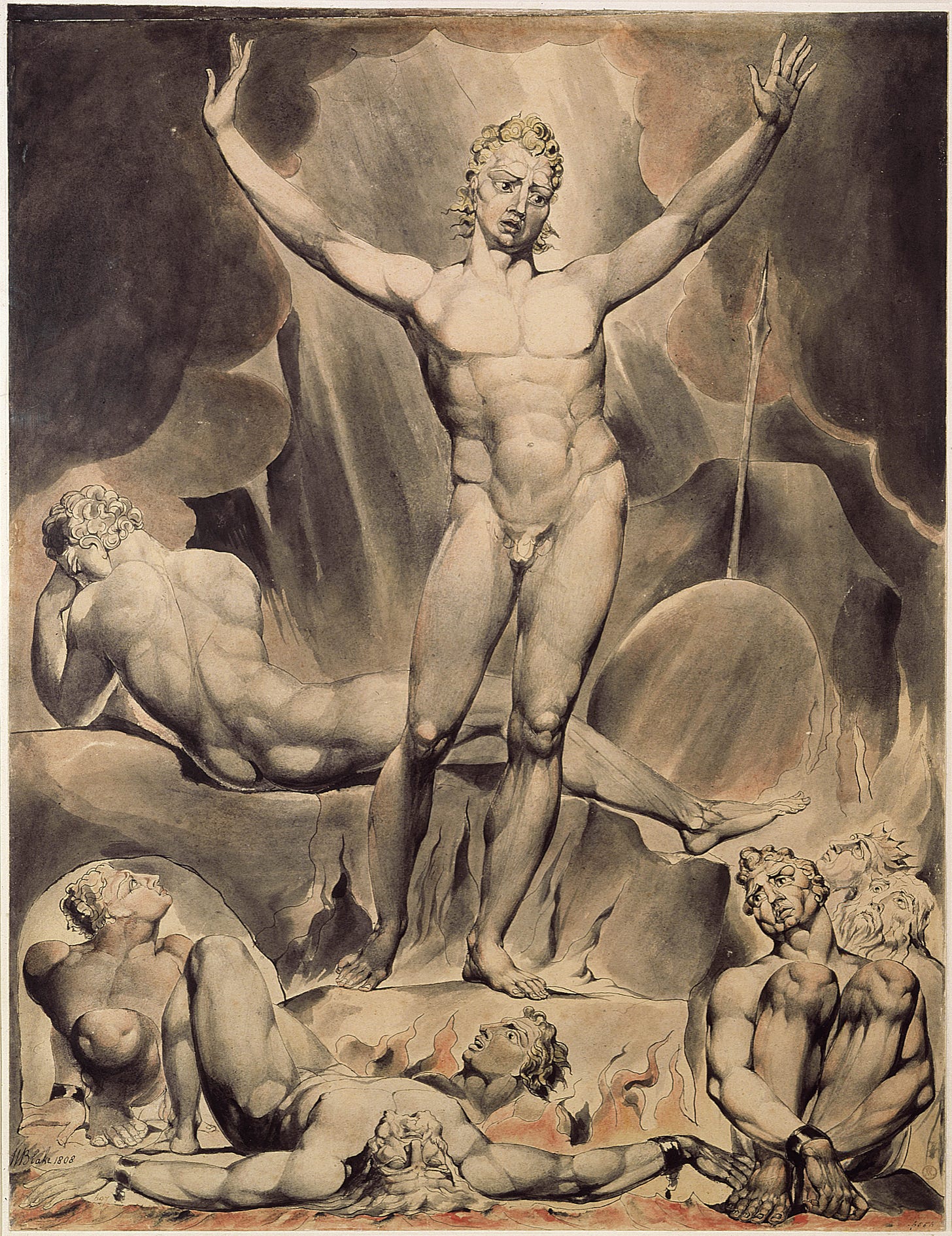

Virtues, and one might take this as a definition, are traits that are to be admired. And there is a great shift from what rationalists think admirable, to what is admirable for the romantics. Take Milton’s Satan, who, after being cast into Hell, still proudly defies heaven, and vows to “make evil my good.” For a rationalist, Satan is to be despised for his love of evil; and as for Satan’s great energy for pursuing evil, and his great power to inspire others to follow, they are only grounds for fearing him, and despising him more: