Robert Bridges was Britain’s Poet Laureate when he made his case against free verse. Published as “A Paper on Free Verse”—not the most poetic title—the year was 1922: the year, ironically or not, of “The Waste Land.” Bridges was swimming against the tide, or a tidal wave. How strong was his stroke?

Bridges first asks what free verse is. The name suggests a negative definition: free verse is poetry not bound by the rules of meter. Bridges finds this inadequate; free verse must have “some positive quality...by which it will be distinguishable from prose.” From then-current theories Bridges takes the idea that “free verse must be rhythmical.” But rhythm is a repeated pattern, and how is rhythm possible without meter? It seems that, to write free verse, one must flirt with the regular rhythm of metric verse, but always shy away, never show the ring, never consummate. Free verse is not really free; the poet “has cast off his visible chains but has not escaped into liberty.” In a funny but (to me) opaque moment, Bridges calls the discipline of free verse “a sort of protestantism.”

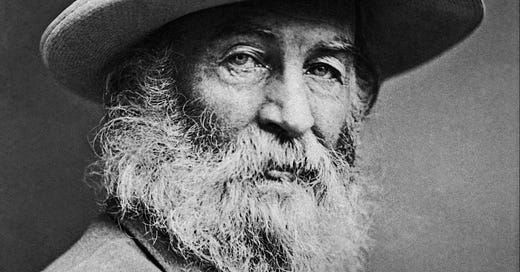

In fact, Bridges asserts, “a great deal of ‘free verse’ has been easily analyzed into the disguise of old forms.” Writing good non-metric poetry is harder than it seems, for efforts to make a line good, often makes it metric, whatever the poet’s intentions. Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself, that radical break with metric tradition that pre-dates Pound and Eliot by more than half a century, begins thus:

I celebrate myself, and sing myself, And what I assume you shall assume

These, the opening lines of a famous piece of free verse are—in iambic pentameter. (The second is a “headless” line, missing the initial weak syllable—certainly allowed, if used more by Chaucer than Shakespeare.)

Of course true free verse, verse that is not iambic pentameter flying under the radar, does exist. Bridges argues that, inevitably, it must