On *Defending My Enemy*:

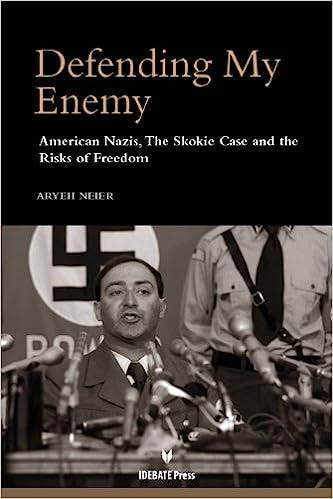

American Nazis, the Skokie Case, and the Risks of Freedom, by Aryeh Neier

At the time, in 1977, the National Socialist Party of America had twenty-five to thirty members, and was led by a man named Frank Collin. Early that year Collin sought permits from a dozen Chicago suburbs, so that his Nazis could hold demonstrations for “white power.” Most ignored him, but the village of Skokie, Illinois, wrote back, telling him that obtaining a permit required a $350,000 insurance bond. Collin responded by calling the ACLU (Aryeh Neier, the author of this book, was at the time its executive director), which sued the city on his behalf, asserting that the insurance requirement violated the First Amendment’s protection of freedom of speech and assembly.

It’s probably unfair to ask what you would do, as head of a Nazi organization, while this lawsuit was pending. Collin did not wait for a decision. Matthew McConaughey has said that “The arrow doesn’t find target; the target draws the arrow”; Skokie had drawn Collin. To him the town had revealed its playbook, and I imagine it was what he had hoped for. He told the city he planned to demonstrate in front of Skokie city hall to protest the insurance requirement, carrying signs with slogans like “White Free Speech.” Collin

took care to inform Skokie officials that the demonstrators would make no derogatory statements, either orally or in writing, directed at any ethnic or religious group. They would, however, march in uniforms. The Nazi uniforms include a swastika emblem on the armband.

Skokie asked the courts for an emergency injunction to prevent the demonstration. The grounds were that

The march...is a deliberate and willful attempt to exacerbate the sensitivities of the Jewish population in Skokie and to incite racial and religious hatred....the public display of the swastika in connection with the proposed activities of the defendant...constitutes a symbolic assault against large numbers of the residents of [Skokie] and an incitation to violence and retaliation.

Roughly half of Skokie’s 70,000 residents were Jewish or of Jewish ancestry. Thousands of them had lost their families to Nazi murder in World War II. Hundreds were themselves Nazi concentration camp survivors.

Skokie’s allegation, note, was that the march would be a symbolic assault. No allegation was made that “the Nazis would engage in violence.” The ACLU’s court filing called this “a classic case in which government officials ask a court of equity to impose a prior restraint on the speech of persons advocating unpopular ideas,” and therefore a by-the-book violation of the First Amendment. The judge did not see it that way, and he gave Skokie its injunction, barring the National Socialist Party