Notes on Caravaggio

...

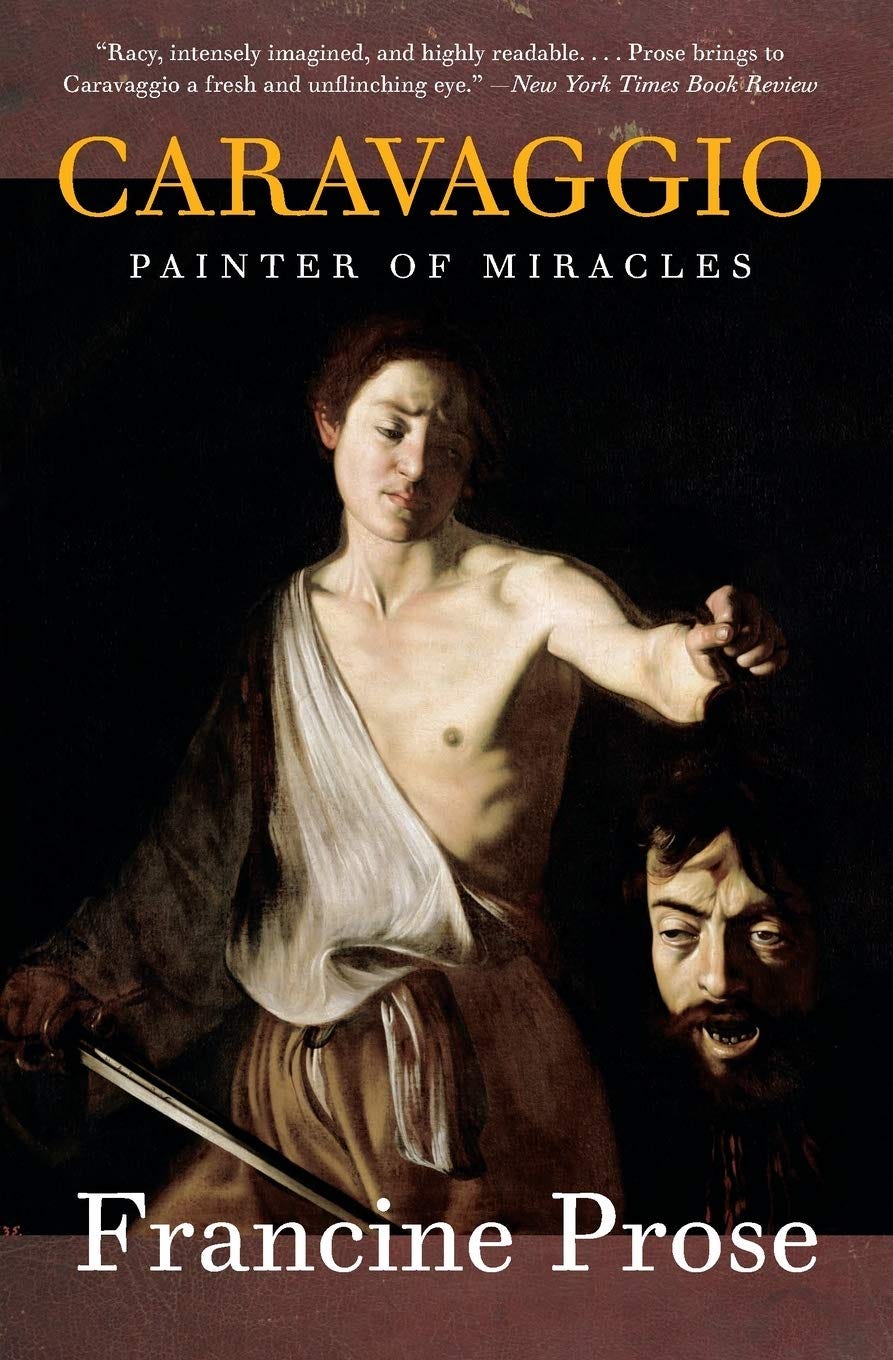

1: Caravaggio, in his religious art, reminded people

that these miracles had transpired neither in primary colors, nor in brilliantly hued paintings of sanitized saints and celestial fireworks, but in dusty streets and dark rooms much like the streets and rooms in which they lived.

That’s Francine Prose, author of Caravaggio: Painter of Miracles. Caravaggio rejected the received opinion, that paintings should aim for ideal beauty, perfect proportion, and classical decorum. He was a Romantic Modernist born too soon, in the late Italian Renaissance. The romantic urge to transgress is apparent in his life too, not just his art: both ask us to accept

that the angelic and the diabolic, that sex and violence and God, could easily if not tranquilly coexist in the same dramatic scene, the same canvas, the same painter. Caravaggio nearly fulfills every popular cliche about the personality of the artist.

Every Romantic cliche, that is. For three hundred years, “his work was despised or simply ignored.” Only since the 1950s has he been truly appreciated.

2: Caravaggio painted from life. Models would be asked to hold the often strange configurations he wished to paint, while he put brush to canvas. An early biographer complained: Caravaggio