Holmes Changes his Mind

The Birth of Free Speech in America

Hob: Nice mustache.

Nob: Oh, thanks, my wife is still unsure about it.

Hob: No, I mean on the cover of that book you’re reading. If I’m not mistaken, that’s the great Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr, blue-blooded Boston Brahmin, thrice-wounded Civil War Veteran, and Supreme Court Justice.

Nob: You have a good eye.

Hob: You know, I’ve never understood how a man who believed that a democratically-elected government could, legally speaking, do more or less whatever it wanted, a man who “disdained all constitutional rights,” came to change his mind, and became the poster-child for First Amendment restrictions on government action.

Nob: Well you should read this book—The Great Dissent: How Oliver Wendell Holmes Changed his Mind and Changed the History of Free Speech in America, by Thomas Healy.

Hob: I tried, but got bogged down in the long descriptions of Holmes’ daily routine, of his vacation home on Boston’s North Shore, the secret affair with a married woman in Ireland, etc. Who cares? The book is supposed to be about ideas, and how some ideas shifted this man’s beliefs. I wish Healy had skipped all the other stuff.

Nob: Well it all started with a chance encounter on a train—

Hob: —See now you’re doing it too—

Nob: —with Judge Learned Hand.

Hob: Is that pronounced “Learnéd Hand”?

Nob: Yes.

Hob: How on earth did he come by that name? If anyone ever confirmed nominative determinism, he does.

Nob: Doesn’t matter, let’s get to the ideas. Hand (who, I do have to add, studied philosophy in college) had recently ruled against the government in a case involving the 1917 Espionage Act.

Hob: The World War I law that criminalized willfully obstructing the draft, and causing insubordination in the military?

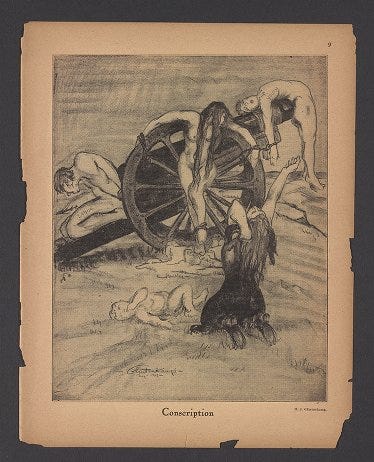

Nob: Yes. The Postmaster General decided that the anti-war cartoons and poems in the leftist journal Masses violated that law, and refused to deliver it through the mail. The editor sued, arguing that the stuff in his journal was protected by the First Amendment.

Hob: Which it obviously was. I mean look at it—I read the internet, that’s pretty tame.

Nob: Not then it wasn’t. But—

Hob: Wait, not tame, or not protected by the First Amendment?

Nob: Neither. But Hand, an anxious and risk-averse man, nevertheless had a kernel of courage in him, and ruled against the government, arguing that, if the government’s claims were correct, they would “contradict the normal assumption of democratic government that the suppression of hostile criticism does not turn upon the justice of its substance or the decency and propriety of its temper.”

Hob: Sounds sensible.

Nob: No one thought so. His decision was immediately overturned on appeal. It remained legal for the Post Office to refuse to deliver writings critical of the war.

Hob: So what happened on the train?

Nob: Hand and Holmes were, coincidentally, on the same train, and ran into each other. Hand, instead of chatting about the weather, decides to make his case to Holmes. Holmes was dismissive, but Hand persisted, following up with a letter. Here’s an edited version: