Comics and the imagination

or, on closure and the gutter

When Henry V opens, the Chorus asks “pardon” for the distance between the reality of what will happen on the stage, and what in response the audience is to imagine:

Can this cockpit hold The vasty fields of France? Or may we cram Within this wooden O the very casques That did affright the air at Agincourt?

Of course not, but then again, with the audience’s cooperation, maybe they can:

let us ... On your imaginary forces work. Suppose within the girdle of these walls Are now confined two mighty monarchies ... Think, when we talk of horses, that you see them Printing their proud hoofs i’ th’ receiving earth, For ‘tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings, Carry them here and there...

The author has summoned up a fictional world, and while reality is a thing we access through the senses, by seeing and hearing and touching, it is through the imagination that fictional worlds are known.

What one is to imagine, when engaging with a story, depends in part on the medium in which the story is realized. If the medium is language, and you are reading a novel written in the third-person, normally you simply imagine what the words say. Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! opens with

From a little after two oclock until almost sundown of the long still hot weary dead September afternoon they sat in what Miss Coldfield still called the office...

and we obedient readers will imagine that, from a little after two until almost sundown, some as-yet-unnamed people sat in that room, etc. We will certainly also imagine more than what the words say—we will imagine also that the room in which “they” are sitting is no longer an office. But it is the base on which this superstructure is built, what one imagines in the first instance, that is the focus here.

If the medium is film, it is harder to specify in writing what one imagines. The sequence of images that constitutes The Wizard of Oz depicts at one point a girl skipping down a yellow brick road with some companions. Audiences, in response, imagine that Dorothy, the Scarecrow, etc are on the road. But “Dorothy is on a yellow brick road” does not do justice to what is imagined: the color pattern on Dorothy’s dress, the way her hair falls, the precise expression on her face—all this information and more is conveyed by the images, and imagined by the viewer; but this content is, as a practical matter, impossible to articulate in words on the page. This difference aside, films and novels are largely the same: the page or the screen presents information about the fictional world, the fictional world is thus-and-so; and audiences well-versed in the practice of appreciating fictions take this as their cue to imagine that things are thus-and-so.

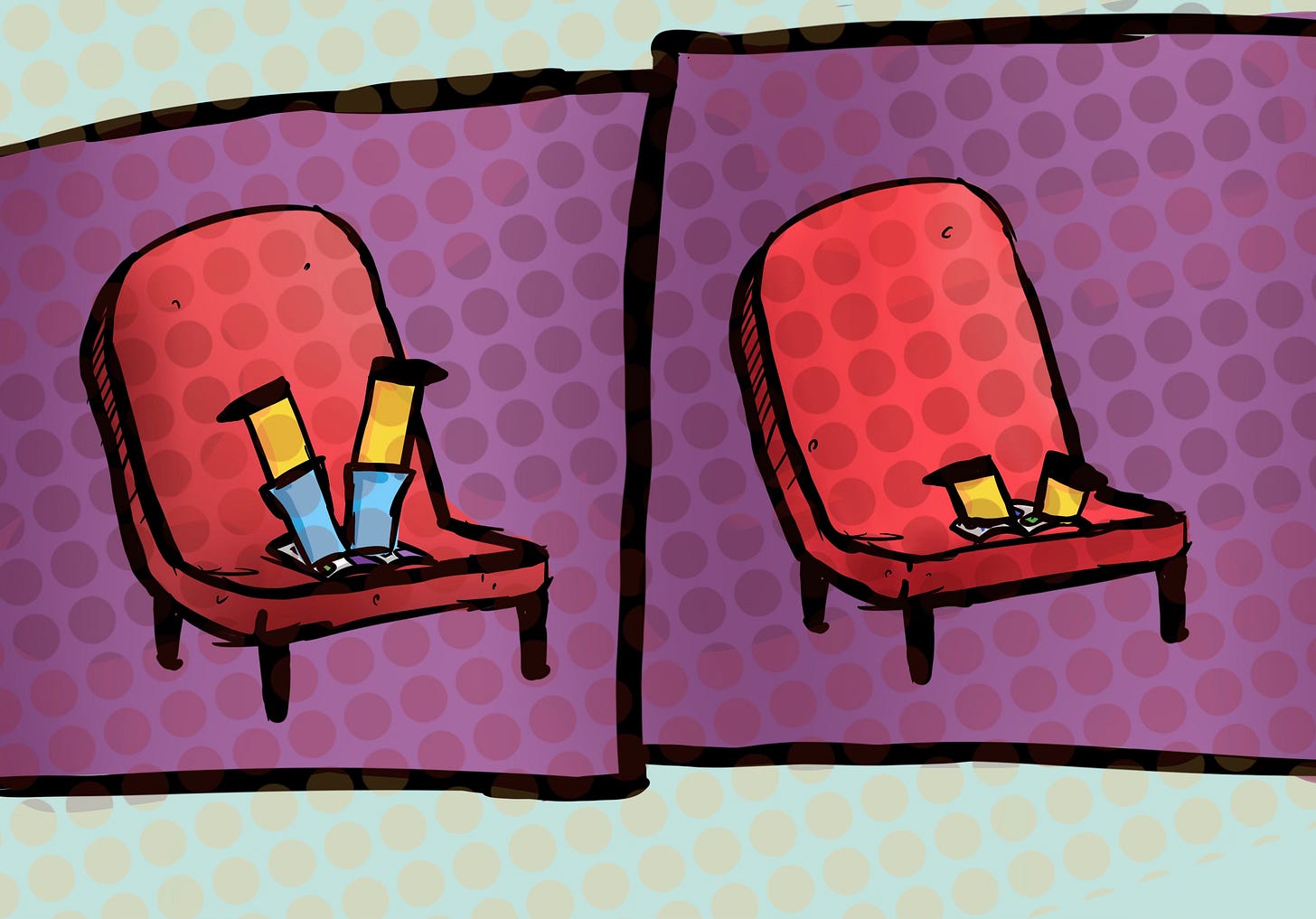

Is it “largely the same” with comics as well? Comics are a hybrid medium, using both words and images-in-sequence—yet unlike film the images are juxtaposed in space. The panels lie next to each other on the page, rather than succeeding each other in time on a screen. The null hypothesis about whether comics are like the others is the yes answer: the “rules of engagement” with comics look much like those for novels and films, instructing you to (i) inspect each panel, and apprehend what information about the fictional world that panel conveys—the panel, say, makes it that the fictional world is thus-and-so; and then (ii) in response, to imagine that things are thus-and-so. Here, for example,