“I rammed him for a good five to ten minutes,” Bowie later recalled, between songs at a BBC concert in 2000. “Nobody stopped. Nobody did anything.”

At a time of such incredible personal turmoil, he was able not just to continue working, but to create some of the most striking, moving, and groundbreaking work

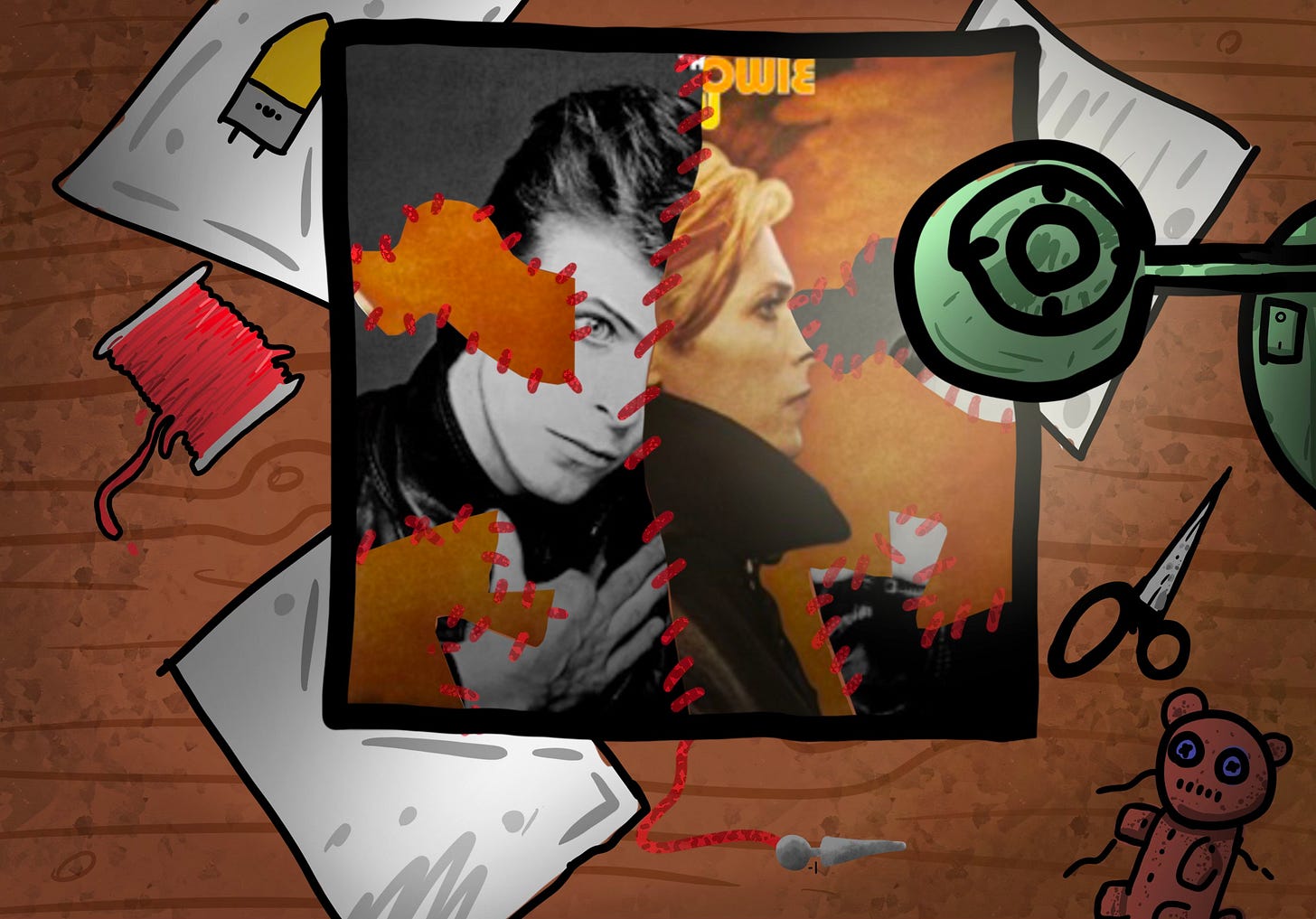

The cover of the live album he released in October 1974, David Live, shows the full extent of his physical deterioration.

This kind of paranoid, drug-fueled rambling would become typical of David Bowie interviews over the next 18 months.

about watching for UFOs (“I made sightings six, seven times a night for about a year”), Mayan civilization, media control and “cultural manipulation”, and Nazism,

It was the first of his albums to abandon, almost entirely, rock ’n’ roll in favour of something funkier and more soulful.

Angela Bowie notes that she “never saw any jugs, jars, vials, or any other containers full of urine

He also read avidly, as ever, having apparently brought 400 books with him for the 11-week shoot.

He would arrive at the studio with little more than a couple of song fragments—in this case ‘Word On A Wing’ and ‘Golden Years’—which he then handed over to bandleader Carlos Alomar. Alomar would then figure out several arrangements of each song with Dennis Davis and George Murray, from which Bowie would pick the one he liked best.

Dennis Davis’s drumming might be metronomic, but is keenly felt, while Murray’s bass is responsive rather than restrictive.

But then Bowie always had, and still has, an almost childlike enthusiasm for thrusting his latest discoveries on anyone

Bowie’s interest in fascism is symptomatic of the very aspect of his character that is most often praised: his near-constant desire to grow and change

As bandleader Carlos Alomar put it some years later, “He’s a pseudo-intellectual. He is what he reads, and at that time in his life, he was reading so much bullshit.”

The point of his return to Europe, as he had decided six months earlier, was “to experiment; to discover new forms of writing; to evolve, in fact, a new musical language.”

“Nobody gives a shit about you in Berlin,”

Bowie, on the other hand, preferred to work in a much more spontaneous fashion.

The Idiot also dispels the myth that Brian Eno led Bowie away from conventional rock and pop music

his decision to work with Eno made more sense. Both had risen to prominence as extravagant key players in the UK’s glam-rock scene, but were bookish and intellectual at heart

Here it was the producer’s turn to impress, describing how his newly bought Eventide Harmonizer “fucks with the fabric of time.”

he new “full well’” that what the singer might initially consider to be demos “could end up as masters, and they did.”

he fed Dennis Davis’s snare drum into his much-trumpeted Eventide Harmonizer, and set it to feed back into itself, at an almost imperceptible delay, with the pitch gradually lowering each time, resulting in a strange, weightless thump that sounds as if it might carry on indefinitely

Bowie told Visconti that he didn’t think it quite right for what he was trying to achieve on Low, but the producer persevered, engaging in a spot of musical subterfuge by turning the effect off in the main studio monitors

Gardiner “was given no instructions whatsoever” as to what he should play, except for “one solo where [Bowie] sang the first three notes

Robert Fripp, meanwhile, would later note that Eno’s approach to record-making is “not governed by musical thinking”,

it was also felt that the fact that Chopin died there of consumption “resulted in Eno developing a cough.”

The most striking aspect of this material is not so much its largely instrumental nature, or its synthetic sheen, so much as its refusal to resort to conventional song structures.

Bowie found himself too physically and emotionally drained to record

Bowie intended each of the seven songs on side one to have words, but in the end failed to write anything suitable for the first and last of them, ‘Speed Of Life’ and ‘A New Career In A New Town’. As a result, both are instrumental,

The music on side one is frenetic and often unresolved, each song fading out inconclusively

RCA executives who considered it to be distinctly unpalatable for the Christmas market.

“Virtually every time I saw him in Berlin,” writes Angela Bowie of the period, “he was drunk, or working on getting drunk.”

In the case of ‘Warszawa,’ however, Eno deserves all the credit he can get, since he effectively wrote and recorded the entire piece himself, but for Bowie’s surprising, freeform vocal.

“the ONLY contemporary rock album.”

“Who needs this shit?” he asks—this shit being “the sound of nothing.”

Everyone from The Ramones to The Damned put Iggy atop the punk-rock pedestal;

“Watching Iggy Pop in 1977 is like watching a film,” he wrote, “He’s not real any more, he’s like a puppet.

As ever, Bowie obliged, declaring punk to be “absolutely necessary [as] a sort of musical enema”,

Somewhat surprisingly, for the first time in six years, he flew, from Heathrow, having belatedly decided that “the aeroplane is a really wonderful invention.”

There’s a looseness not present on any of the other records either of its principal authors made at the time, best exemplified by ‘Success’

Iggy came up with a lot of the lyrics and vocal melodies on the spot

His Low, however, for all its unquestionable artistic merit and pronounced effect on what followed, was a very insular record

“I thought, ‘Shit, it can’t be this easy.’” But it was. Most of the rhythm tracks heard on “Heroes” are first takes.

Of all of Eno’s interventions on “Heroes”, the one that drew the most resistance was the deployment of his Oblique Strategies. These are contained on a set of around 100 cards he first produced in 1975 in collaboration with the artist Peter Schmidt; each features a non-linear instruction designed to help the musician or artist in question overcome a creative block. “The kind of panic situation you get into in the studio is unreal,” Eno said in 1978. “The function of the cards was to constantly question whether [the direction the music took] was correct. To say ‘How about going that way?’”

prior to the release of the fifth edition, in 2001, older decks were changing hands for up to $1500 on ebay.

Despite the fact that they found themselves in what was, essentially, a tiny enclave of Westernism deep in Soviet-controlled East Germany, overlooked by border guards, the musicians involved felt less isolated

The arrangements on “Heroes” are, by and large, much more atonal and confrontational than anything on its predecessor, with noisy, distorted, multi-tracked electric guitar very much at the forefront

Fripp famously recorded his guitar parts for “Heroes” at a pace that rivaled even Bowie’s rhythm section.

From there he simply started playing, apparently without having heard the songs first. Bowie, as ever, resisted the opportunity to give the new arrival anything approaching a tangible instruction, suggesting only that he “play with total abandonment, and in a way that he would never consider playing on his own albums.”

with that, the first side of “Heroes” was, for all intents and purposes, complete—except, of course, for the lyrics, to which Bowie had not yet given any thought whatsoever.

each would record a track (or several) on his own and then, before the other added his, push down the sliders, leaving them both unsure as to exactly what they were working with.

there is also a sense beneath the surface of them being created by a pair of musicians delighting in playing musical tricks on one another

Bowie’s vocal performances are magnificent throughout, switching effortlessly from histrionic falsetto to low, warm, conversational tones. From a pure singing perspective, he had never sounded as good, and perhaps never would again.

Living in Berlin, Bowie had told Rock Et Folk immediately before the “Heroes” sessions began, had taught him to write “only the important things”.

The five-song suite that makes up side one, in fact, is perhaps the strongest sequence of songs on any Bowie record. But in terms of overall canonical importance and sheer artistic bravery, Low has the overwhelming advantage of having been released first

This is one of my favourite eras of Bowie. Both the music and the all the surrounding things that accompanied it. Truly fascinating! This was a wonderful piece that will have me exploring the Berlin trilogy again! So thank you!