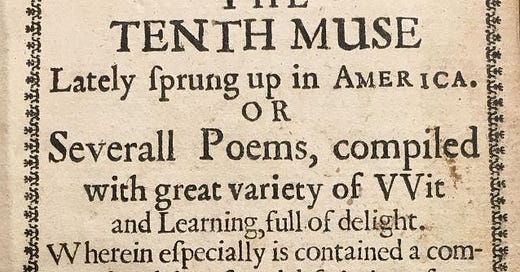

Anne Bradstreet was born in England, and raised near Old England’s Boston. In 1630, when she was eighteen, her family crossed the Atlantic on the Arbella, and helped John Winthrop found Puritan New England. There she would become America’s first great poet. Bear in mind the harsh conditions under which she worked. Only ten years had passed since the first Pilgrims arrived at Plymouth; this was frontier living. Bradstreet bore eight children, and wrote her poems in “a few hours snatched from sleep and other refreshment.” I cannot imagine.

1. What were Bradstreet’s poetic achievements? Her work is uneven—the later stuff is better—but the best of it is fine indeed. Bradstreet wrote, of course, in meter, iambic tetrameter and pentameter, and every practitioner of the form knows the challenges of placing polysyllabic words in an iambic line. Struggling poets tend to shun them, producing results that fit Alexander Pope’s complaint in An Essay on Criticism: “ten low words oft creep in one dull Line.” When used well monosyllabic lines can have magnificent effect, as in Tichborne’s elegy (1586):

My prime of youth is but a frost of cares, My feast of joy is but a dish of pain, My crop of corn is but a field of tares, And all my good is but vain hope of gain.

But it’s no accident that Milton showed off his chops by layering polysyllables without breaking the meter:

Unmanly, ignominious, infamous

Exasperate, exulcerate, and raise.

(Both from Samson Agonistes.) This Bradstreet could also do. In her Dialogue Between Old England and New, Old England explains the cause of her current crisis:

Idolatry, supplanter of a Nation, With foolish superstitious adoration.

2. For lines about the English monarchy in decline, Shakespeare is undefeated; but Bradstreet is in the lists with this couplet, especially the final phrase:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mostly Aesthetics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.