1. The institutional definition of art

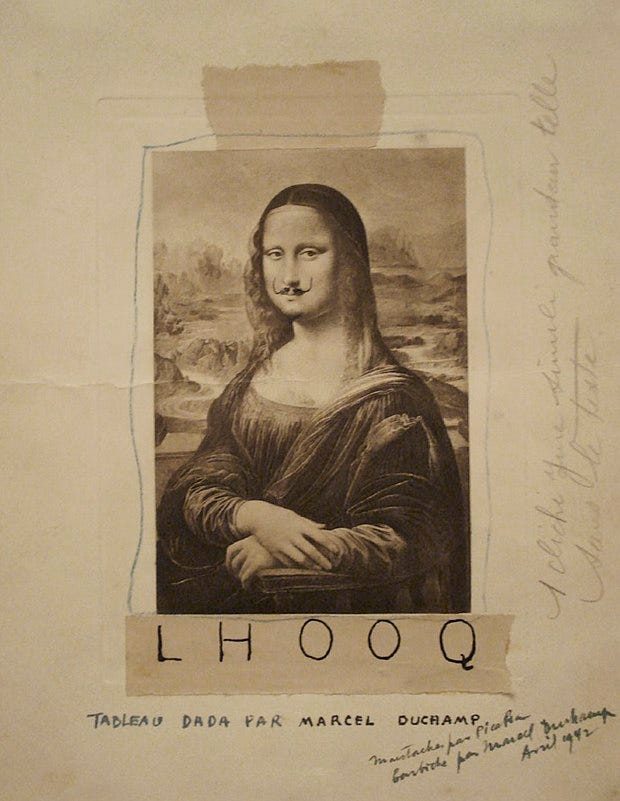

Plato held that works of art were imitations of reality. Unchallenged for two thousand years, his definition was rejected by the Romantics, who said that art was an outpouring of passion or emotion. The pace of artistic revolutions increased; so too did the rate at which definitions of art were proposed. Duchamp’s readymades marked a turning point: Fountain was a stock-made urinal, In Advance of the Broken Arm was a stock-made snow shovel, and L.H.O.O.Q. shaved was a postcard reproduction of the Mona Lisa on which he had not drawn a mustache. Despite being indiscernible from similar urinals, shovels, and postcards not touched by famous artists, these were works of art. Neither the art-as-imitation nor the art-as-expression definition could explain why, and both therefore stood refuted.

After the usual delay between a change in a social practice, and that change’s impact on philosophical understanding, the institutional definition of art was proposed. Any institution creates various status-positions. The United States Government defines the status of US legal tender; the Catholic Church defines the status of saint; you get the idea. The institutional definition of art postulates an institution, called “the artworld,” and says that work of art is a status that it defines. Earning that status, therefore, involves having that status conferred on you, in accord with the institution’s rules. Fans of the institutional definition rarely describe those (alleged) rules in detail, but a natural idea is that, just as one becomes a knight when the King or Queen taps you with a sword and says “I dub thee Sir So and So,” a thing is elevated to the status of work of art when an agent of the artworld—the most familiar of whom are people we call artists—take that thing, and it can be anything, from a painted canvas to a urinal from Home Depot, and says, presumably silently in their head, that this thing is now a work of art.

The radio show Schickele Mix once played a skit about Beethoven walking the gardens with an underling. He (the underling) pointed out to the great composer a moment in one of his string quartets with parallel fifths (two instruments staying a fifth apart as they change notes), a no-no according to the rules of classical composition. Beethoven, in a booming voice, responds “AND WHO HAS FORBIDDEN IT?” This joke, taken straight, is the institutional definition: Beethoven is an agent of the artworld, and no minor player; he holds an important position and has accumulated great power. Whatever rules the institution might have against parallel fifths, Beethoven, using his authority in the artworld, can suspend or even eliminate them, with just a word.

But is the institutional definition right? If so, you would expect that when an artist makes something into a work of art that everyone thinks breaks the rules—everyone thinks it fails to be a work of art—the artist would simply respond, “it doesn’t matter what you think, it is art simply because I say so.” Maybe the Duchamp examples look a little like this (I haven’t read any Duchamp biographies). But others do not.

2. Free Verse

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Mostly Aesthetics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.