All the Fun’s in How You Say a Thing by Timothy Steele: Review and Refutation

Part 2 of Theory of Meter

This is a stand-alone essay, but if you’re curious you can read Part 1, Against Feet Revisited.

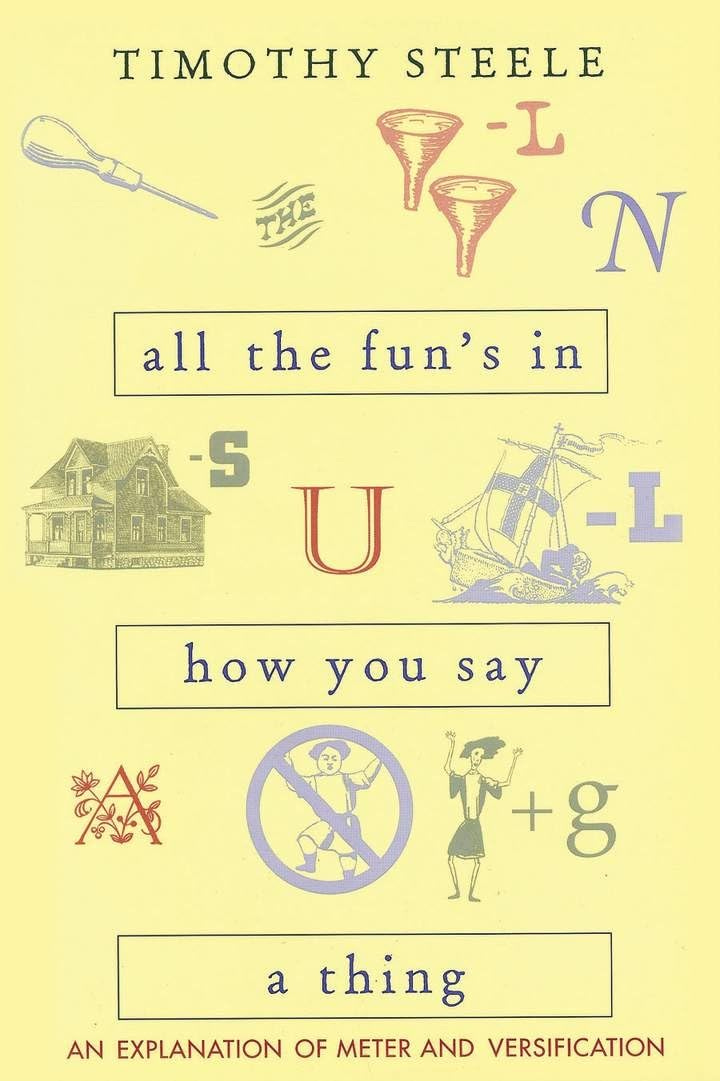

1. Timothy Steele’s book All the Fun’s in How You Say a Thing aims to offer “an explanation of English meter,” especially iambic pentameter. That meter is flexible, more flexible than is often thought: this conviction is Steele’s north star. Imagine the complete range of rhythms, metrical and not, that a ten-syllable line may instantiate, to be a backyard pool. Are those that conform to the demands of iambic pentameter a tiny buoy you can barely hold? No, Steele asserts, they are a spacious inflatable raft, with room to stretch and pose.

On this point Steele is right. That’s the good part. The bad part is that he’s wrong about what iambic pentameter is. I love Steele’s poetry. I loved this book the first few times I read it. And despite being wrong about a central question, the book is well worth reading. Steele’s discussion of the ways poets exploit the possibilities of meter, for poetic effect, has much to teach. Be that as it may, this essay focuses on the book’s errors.

2. So what is iambic pentameter, on Steele’s account? The answer has two parts. First, there is a “basic norm or paradigm” for the meter:

unstressed STRESSED unstressed STRESSED unstressed STRESSED unstressed STRESSED unstressed STRESSED.

It will reduce confusion (trust me) if we write the paradigm instead like this:

W S W S W S W S W S.

It consists of ten alternating “weak” and “strong” positions.

Second, a line of verse is in iambic pentameter if it “realizes” this pattern. So when does a line realize the pattern, and (more importantly) when does it fail? A first pass (to be corrected) at the core part of the answer is this:

(*) If the stresses in a ten-syllable line alternate unstressed-stressed, it realizes the pattern.

Note this is an “if,” not an “if and only if”: there are other, less central, ways to realize the pattern. But before getting to any of that, (*) must be made more precise; it is not quite what Steele says.

3. Consider the line of iambic pentameter (by the poet Jones Very)

No selfish wish the moon’s bright glance confines.

Which syllables are stressed, and which unstressed? If we use capitals for stressed syllables, then this is a good answer:

No SELfish WISH the MOON’S BRIGHT GLANCE conFINES.

That’s got three stresses in a row, so does not satisfy condition (*). It may seem, therefore, that this line realizes the iambic paradigm some other way.

Steele thinks this is partly right but mostly wrong. Very’s line is not, on Steele’s view, an unusual instance of iambic pentameter; instead, (*) does not correctly articulate the central way of realizing the iambic template. It wrongly ignores two facts: first, that syllable stress is graded, not binary; and second, that to test whether a line is metric, it must first be divided into feet.

I will take these in reverse order. To divide a line into feet, one groups sequences of syllables in the line, so that each syllable is in some group. The syllables in the line above may be grouped into two-syllable feet as follows:

[No self-] [-ish wish] [the moon’s] [bright glance] [confines].

Now, regarding stress. Syllables do not fall categorically into two distinct buckets, “stressed” and “unstressed.” There are intermediate levels. For example, in “congregation” (con-gre-ga-tion), the first syllable is the most strongly stressed, the second and fourth are un- or weakly-stressed, but the stress of the third is somewhere in between. To capture this, Steele labels the stresses of syllables with the numerals 1 through 4; but this is meant to be a convenience; degrees of stress are finer than this.

Once we recognize degrees of stress and foot division, we can define four two-syllable feet:

* The iamb: first syllable weaker than the second.

* The trochee: first syllable stronger than the second.

* The spondee: both syllables equally strongly-stressed.

* The pyrrhic: both syllables equally weakly-stressed

It’s crucial to note that these definitions refer to the relative stresses of the syllables in a foot, not to their absolute stress levels (or their stresses relative to their non-foot neighbors). A foot, therefore, can be an iamb, even if both of its syllables are strongly-stressed—as long as the second is more strongly stressed than the first.

Now we can state Steele’s preferred alternative to the condition (*):

(**) If a line consists of five iambs, it is in iambic pentameter.

Very’s line (repeated here) did not meet condition (*), but it does, Steele claims, meet (**).

[No self-] [-ish wish] [the moon’s] [bright glance] [confines]

“Bright glance” is, Steele says, an iamb: “bright” is stressed, but not as strongly as “glance.”

4. Is Steele’s claim about these stress levels true? When I say Very’s line to myself, I feel like I, as it were, hit the words “bright” and “glance” equally hard. If that’s right, then “bright glance” is a spondee, not an iamb. Before trying to judge between these options, it’s worth asking why it matters.

If “bright glance” is a spondee, then Very’s line consists of three iambs, then a spondee, then another iamb. If so, then a line can “realize” the iambic paradigm even if one of its feet is a spondee. Are we arguing about the analysis of this line, because Steele denies the possibility of spondees in English, or their acceptability in iambic pentameter? It turns out he denies neither. He accepts the Queen Gertrude’s line to Hamlet,

Come, come, you answer with an idle tongue,

has a spondee in the first foot (“come, come”), and is in iambic pentameter. It is not an isolated case. This line from Henry IV Part 2 opens with two spondees:

East, west, north, south, or, like a school broke up [...]

So Steele dwells on alleged examples of spondees not for theoretical reasons—not because he denies that iambic verse may contain spondees—but for practical ones. True spondees (and pyrrhics as well) are, he thinks, rare, and one should therefore hesitate to think one has spotted any:

authorities introduce them [spondees and pyrrhics] almost willy-nilly into accounts of poems in conventional iambic measure [by which he means, poems whose lines in fact satisfy (**)].

As it happens, I don’t think the examples he uses to support this claim are all that “willy-nilly.” He mentions the line from Yeats,

An agéd man is but a paltry thing,

and complains about a critic scanning the third foot as a pyrrhic:

[An AG-] [-ed MAN] [is but] [a PAL-] [-try THING].

Steele “hears” the “but” as stronger than the “is,” but I find the case hard to judge, and you should admit that you do too. (Note that intuitive judgments about stress will be dismissed below as unreliable.)

Steele’s war on spondees has a second, and to him more important, practical motive. He thinks that, if very many lines in iambic pentameter fail to satisfy (**)—and so must satisfy some “variant” condition that qualifies them as metric—, then

readers...who are young and unfamiliar with verse...may wonder why iambic pentameters...are so named, since so few of them will appear to conform to the pattern they ostensibly embody. Moreover, scansions full of pyrrhics and spondees may lead young poets to think that any and all substitutions have always been permitted at any point in the line. Such scansions suggest as well that poets who wish to write conventional iambic pentameters are thereby doomed to construct lines according to the two-syllable-per-phrase model,

and thus such poets will think that only a quite restricted range of rhythms are allowed in iambic meter, and that interesting rhythms in poetry are only achieved by breaking the rules. It’s at this point that Steele, usually cool as a cucumber in his writing, comes close to getting angry:

The unhappiest consequence of the idea that meter is most interesting when violated is that it may seduce poets into making a virtue of clumsiness. If the conventional line is thought to be monotonous, and if departures from it as views as beneficial, poets may come to see their inability to control the medium as an indication of technical subtlety.

I agree: it’s bad if poets think there’s no virtue in mastering metric verse; it’s bad if they think that, since great poetry must break those rules, the rules aren’t worth knowing. But that’s not an argument that “scansions [of ‘conventional’ iambic lines] full of pyrrhics and spondees” are wrong! The truth may have bad consequences. And it’s ironic that Steele worries that such scansions, if correct, will cause readers to wonder why iambic pentameter is so-named. Maybe it is poorly-named. I think it’s poorly-named. It is not a “rule” of iambic pentameter that a line should ideally consist of five iambic feet. (See section 10 below.)

5. The last section asked whether “bright glance” (considered as a foot) is an iamb or a spondee. I think this is a bad question, because I think the framework of “feet” is a bad one. But if you do like that framework, your opinions about this case should be weakly-held.

What is stress, anyway? The consensus among scientists of language is that stress is a somewhat theoretical notion. It is not a “surface feature” of a language. The pitch (high or low) of a syllable when spoken, and its duration (length), are cues to its stress-level, but stress cannot be reduced to either. Here is what Bruce Hayes says, in his book Metrical Stress Theory:

the relation between stress and pitch/duration is both indirect and language-specific, [and so] it is impossible to “read off” stress contours from the phonemic record....[stress] has no consistent physical correlates.

prosodic phenomena are among the least accessible to consciousness. For example, teachers of beginning phonetics often encounter students who, although native speakers of English, simply cannot hear where the main stress of an English word falls.

The study of stress, he concludes, should have “little recourse to intuition.”

6. What’s the alternative? Accurate conclusions about degrees of stress will require the application of some theory; one cannot just use one’s inner “stress sense.” Once we do apply some theory, I actually think Steele is right about “bright glance.” First, in general (I gather from the little linguistics I’ve read on this topic), a noun (here, “glance”) usually bears more stress than an adjective that modifies it (“bright”). Second, when three stressed monosyllables occur in a row (as here in “moon’s bright glance”), the stress on the middle word is “demoted” slightly relative to the other two. (Steele mentions both of these conditions.)

But if Steele is right that “bright glance” is an iamb, and so that this line satisfies (**), about other cases he is less persuasive. When Adam in Milton’s Paradise Lost “laments that the blame for the corruption of human kind falls”

On me, me only, as the source and spring,

The second foot might appear a spondee, or maybe a trochee (“On ME, ME ONly”). Steele claims, to the contrary, that the first syllable of “only” is more strongly stressed than the second “me,” for rhetorical effect. But I’m not convinced.

7. Speaking of trochees, “trochaic substitution” (the appearance of trochaic feet) in iambic verse is common, as Steele himself discusses. When are they allowed?

Trochaic substitution is rule-governed; you can’t just insert as many as you want, in any context, and still have an iambic line. So Steele’s theory must have some condition

If a line consists of iambs and trochees, and [...], then the line is in iambic pentameter,

where what fills the blank describes the circumstances in which trochees are allowed. Steele fills in the blank in the conventional way, so that (i) trochees are always allowed in the first foot; and (ii) trochees are allowed elsewhere, if they follow a grammatical pause. He illustrates the second of these with a line from Spencer:

The joyous birds, shrouded in cheerful shade.

The word “shrouded” is a trochee, and follows the pause after “birds.”

But in fact trochees are allowed in more circumstances than Steele’s (i) and (ii) cover. Consider

Resembling strong youth in his middle age. (Shakespeare, Sonnet 9)

Dividing this into feet, it becomes

[Resem-] [-bling strong] [youth in] [his mid-] [-dle age].

Here “youth in” is a trochee, but it is the third foot, not the first, so (i) does not apply, nor, as (ii) would require, does it follow a grammatical pause. Again, in

On looking at it with lack-luster eye (from As You Like It) [On look-] [-ing at] [it with] [lack-lus-] [-ter eye].

Here “lack-lus-“ is another mid-line trochee not preceded by a pause. Examples multiply; yesterday I came across the trochee “weeps from” in

The blood weeps from my heart when I do shape (Henry IV Pt 2).

Two more from the same play: “not that” in

Presume not that I am the thing I was,

And “you, fath-” in the line

In which you, father, shall have foremost hand.

Steele does discuss examples similar to these, but resists them: “in light of logic, the feet…are trochaic…The ear, however, may hesitate to accept this judgment…The feet may well be trochaic, but they are not as emphatic as the trochees [proceeded by grammatical pauses].” I don’t know what to make of that—my ears report no hesitation. Whatever it does mean, it’s too fuzzy to qualify as an adequate explanation of why these lines, despite their trochaic substitutions, are still in iambic pentameter. It has the sound of special pleading. Steele also says that these troublesome trochees are encountered only “occasionally,” implying that they are marginal cases; but I ran across three in Henry IV Pt 2 during one random evening’s reading. (Indeed, the very first line of Paradise Lost contains one: “first dis-” in “Of man’s first disobedience” is a trochee.)

8. Could Steele add precise clauses, a (iii), (iv), and (v), to the rule about trochees, that would cover these cases? The answer is no, for there are lines with identical foot-patterns to the lines above, that are not in iambic pentameter. Both of the following, for example, are iamb iamb trochee iamb iamb, and in neither does the trochee follow a pause (and both seem equally “emphatic”):

Resembling strong youth in his middle age [yes, iambic pentameter] Resembling a youth in his middle age [not iambic pentameter]

(If you are a Steele sympathizer, you should already think that “-ing a” in the second line is a “weak iamb,” rather than a pyrrhic foot.) So the difference in acceptability between the two lines cannot be described in the framework Steele accepts—that is, in terms of the feet making up the line, and the locations of pauses in the line.

9. It’s possible Steele might shrug off this problem. He writes, at one point, that

In theory a poet may substitute one type of foot for another at any point in the line, such substitutions being permissible as long as they are not so frequent that they undermine the line’s metrical integrity.

So Steele might say, about the “Resembling a/strong youth” examples, that one of them has a third-foot trochaic substitution that undermines the line’s metrical integrity, and the other does not. And I suppose that would be true. But if that’s all that can be said in the “foot substitution” framework about why only one of the lines is metrical, then the framework has broken down; and to aspiring poets wondering how to maintain the “line’s metrical integrity,” it has no further advice to give.

10. Theories never die natural deaths, they must be murdered by dashing young upstarts from the margins of society: that was Thomas Kuhn’s insight. Criticizing the foot-based system Steele prefers will only spur its defenders to spin up more epicycles, unless some better alternative is proposed. Some have indeed been proposed by linguists. Here is an outline of an idea that many of those proposals share. (This follows Hayes, “Metrics and Phonological Theory.”)

Below the fold, an alternative to Steele’s theory is sketched, its explanation of the problem cases for Steele are discussed, and its virtues over Steele’s theory are described.